Peter Broderick, one of the world’s leading experts on documentary distribution, continues his discussion with OWC Host, Cirina Catania. In this episode, he focuses on FESTIVALS. He explains how, when, where and why you might want to submit to festivals (or not), and gives us a primer on the new hybrid systems, including virtual screenings.

Peter Broderick consults with independent filmmakers and companies needing to hone their strategies. He helps design and implement customized strategies to maximize revenues, audience, and impact. Read his articles and subscribe to his Distribution Bulletin at www.peterbroderick.com.

Visit Supercharge Your Distribution for more information on his highly-rated workshops with his partner Keith Ochwat.

In This Episode

- 00:09 – Cirina introduces Peter Broderick, formerly with Paradigm Consulting. Peter is one of the world’s leading distribution strategists, specializing in the documentary genre.

- 03:38 – Peter talks about the film festivals that went virtual. One of them is CPH:DOX, which hosted a successful virtual film festival.

- 08:18 – Peter explains how CPH:DOX was able to do screening for 150 films virtually with the company Shift72.

- 14:27 – What are some of the advantages of a virtual film festival? How can filmmakers benefit from them?

- 19:48 – Did rules and regulations change with the transition from in-person to virtual film festivals? What is a secret screening?

- 25:15 – Peter explains why filmmakers may consider not qualifying for Academy Awards in order to help their career.

- 30:28 – Cirina and Peter talk about the budget and expenses of submitting films to film festivals.

- 32:52 – How to submit a film to Peter? What are the requirements?

- 34:30 – Peter advises the ideal length of a film to submit to film festivals.

- 37:25 – Visit Peter Broderick’s website, peterbroderick.com, to sign-up for their cutting-edge, virtual crash course – Supercharge Your Distribution.

Transcript

As I promised you, This is part two with Peter Broderick, who is our distribution strategist. He’s the former president of Paradigm Consulting and a longtime expert on distribution strategies customized to help independent documentary filmmakers maximize their revenues, audience impact and help their career get way off the ground and into the stratosphere. And he’s got a long track record with that. Peter, welcome back. Thank you for putting up with us one more time.

It’s great to be back, Cirina.

I really enjoyed our last talk. And there was so much information there that as I promised our listeners, I get you back. Festivals have changed, and they are evolving now. So tell us how you feel about using the festival circuit in general for promoting your films?

Well, let’s go back to before there were virtual festivals permitted when we had physical film festivals. For documentary filmmakers, festivals are not essential. They can be helpful, for sure. But a number of films I’ve worked on that have never gone to a single film festival have been wildly successful. And I think sometimes filmmakers think that festivals are way more powerful than they actually are. With fiction, filmmakers’ festivals are more important unless you’re making zombie movies. I think festivals are really significant. But what’s happened is that starting in 1933, it was the founding of the Venice Film Festival. From then until the spring of 2020, which is almost headed toward ninety years, festivals didn’t change. The idea was you’d have a few days or maybe a week in one location, and a lot of movies would get shown. And then a year later, you’d be back in the same location around the same time, and new movies would be shown. And at various points. People approached me at the Rotterdam Film Festival in the late 90s. So they were really interested in the idea of reinventing festivals. And I said, “Well, that’s great because the limitation of festivals is they’re in one location, once a year, and they have an audience that’s limited to the people that can actually get to that location.” And I already could see at that time that there were things that can be done online if you wanted to reach a wider audience. Well, people talked about it, but nothing changed. And then, Coronavirus appeared, and physical festivals were too dangerous. That’s what the case is right now. So they stopped. So at that moment, festivals were forced to make changes, to try to reinvent festivals, and come up with a model that could work online. And some festivals cancel, other festivals postponed, and some festivals became virtual. And the festival that I know the most about that became virtual that was wildly successful is a festival in Copenhagen called CPH:DOX. And they had been around for 14 years as a physical festival. And they’re probably the second most important documentary festival in the world. But they didn’t know in early March what was going to happen with the virus. And then one night, the festival team is gathered around some monitors watching the Prime Minister talk on television. And she said she was closing the borders, and they realized that that was the moment they were going to have to decide whether they were going to not do the festival at all or go virtual. They decided that night to go virtual, knowing that that night was the last night they could gather from that point on. They were all working from home. And somehow, in six days, they were able to convert the festival from a physical model to a virtual model. They showed 150 films, and you could buy tickets online for €6; they could sell up to a thousand tickets a film. And the festival could get extended because once something’s virtual, whereas you couldn’t extend a physical festival where you’ve got buildings and rentals and all that stuff. For the virtual festival, we can just say, “Okay, let’s go another month.”

By popular demand.

Right, which is essentially what they did. And ended up at the festival was really successful, they had the biggest audience ever. The audience in Denmark, in the past, mainly people in the Greater Copenhagen area, attended the festival. But now it was virtual, and people throughout Denmark could connect with the festival. So they diversified their audience, and going forward, now they have a bigger base to build on in the future. And one of the most interesting things they learned was what kind of special events you can do. So the example is, Edward Snowden was going to Skype into the physical festival, and there would be a room with 620 seats. And he was going to be speaking in discussion after the film. So once the festival became virtual, they weren’t limited by 620 seats. And when the event was live, over 2000 people around the world were watching it. And since then, more than another 90,000 people have seen it. So they went from 620 seats to more than 92,000 people seeing that film have seen the discussion. And that shows the exciting possibility of being global. And they monetized it, the initial live event, but after that, it’s been free. But if you think about it, if they charge $1 a view, that’s that could have been $92,000. And so, now we think about, okay, before festivals were limited to people in that town. And now festivals can be limited to a country, a continent, or be entirely global. So it’s a whole new set of possibilities. And my firm conviction is that once people are doing virtual festivals, and learning the advantages and opportunities, that when they have the ability to be physical again, they’re going to become hybrid because they’re going to save the special opportunities that virtually provide and add to those the old opportunities that they knew from physical festivals. And those festivals will be the best festivals we’ve ever seen.

I would bet. There’s a question that comes to mind. I don’t know if you know the answer to this or not, but it’s occurred to me. When CPH:DOX changed to a virtual model, where were they housing the media, so people see it? Do they put it up on YouTube? Was it on Vimeo? Did the media live on their site? I’m wondering if you know the answer to that question.

Yeah, I do know the answer. There’s a company called Shift72, and they’re based in New Zealand. And they were able to put all of the films online in 18 hours, all 150 films. And so the panels during the festival ended up on YouTube. The actual films were screened through the festival’s platform that Shift72 has successfully built.

There you go. Okay, that makes me feel a little more secure–pun intended. That and also festivals are notorious for having cutting edge content, depending on the festival, of course, and some of that cutting edge content might get censored if you go on to a public platform. So it’s nice to know that there are companies like this company in New Zealand that can help do that.

Well, also in terms of piracy, Shift72 software is state of the art but having said that, and I assume most of your listeners know this, however good your anti-piracy software is, there’s nothing to stop somebody from filming a film on a monitor.

Of course.

But anyway, they did a great job, and now Shift72 is going to be doing the Toronto Film Festival, the Sundance Film Festival, and I think the New York Film Festival because they’re the best in the world.

Yeah, I know we had had trouble with piracy many, many years ago. I mean, it’s been going on forever. There’s always a way for somebody to sneak a copy of the film. But I am recalling a couple that was standing in line overnight to see a film in Berlin at the Berlinale. And I asked them why they were going to see the movie and why did they spend the night, and they said, “Oh, we’ve seen it at home several times, but we really want to see it in the theater.” Because they had pirated the film, and that’s hard to do in Germany, by the way. But they had somehow figured out using torrent software, and they had pirated the film, but they liked it. So they wanted to see it in the theater, and they were paying to go into the theater to see it. And also, I think that a lot of people who pirate these movies, not all of them are reselling them. It’s still scary, though. I mean, I’m a member of The Producers Guild, and we do worry about this very much. Yeah, I think that with companies like this around, it makes the virtual screenings a lot more safe and a lot more comfortable for us as producers. So that’s good.

But when I’m asked by filmmakers about piracy, generally what I say is that piracy in your top 20 problems as an independent filmmaker, piracy is not on the list. But obscurity is right near the top. So I would worry a lot, a lot more about obscurity than piracy. And I think there are situations where films have built some kind of awareness by being available that way, and then it’s actually enhanced their ultimate distribution. So I think there’s a set of folks that torrents all the time, and we’ll continue to do that. But most people I know, that’s not something that’s part of their lives.

So if somebody is an independent filmmaker, and they do want to participate in either the virtual or the hybrid situation, what advice do you give them about the kind of team that they need to put together to help them do that?

Well, that’s an interesting question. Because in the physical model, in-person networking was a very big component of a film festival. And in the virtual model, the same thing isn’t true. So I think that you have to think about a couple of things, which is, to what extent you can use the fact you’re in this festival, this kind of seal of approval in a way. To what extent you can reach out to the press, and I don’t count on the festival press office to do it for you. And then, in terms of distributors to be proactive there. So if you’re going to a festival, and it’s been around for years, they’re going to have a list of which press people were at their festival last year. Maybe they’ll even have the list of who’s going to be there this year, even if it’s virtual. Same way with industry, I know what distributors regularly go. So I think one of the first things that a filmmaker should do is get a list of press and industry that were there last year, and if they know what it’s going to be, then they can have the opportunity to reach out to those people directly. Secondly, I think that festivals are beginning to develop ways to allow a kind of virtual networking. I know, the CPH:DOX, when they were on the conference side, they created a waiting room, where people who were in between Zoom meetings could hang out. So it was distributors and financiers. And then those people while there was a way for them to network with each other. So I think we haven’t totally figured this out yet. But I think there’ll be possibilities to do that. And then also, when a filmmaker is in festival mode, or conference mode if they can do a one on one or one distributor in their Zoom. I think that gives them the possibility of maybe a higher quality contact and just running into somebody to party.

Absolutely. Well, and they’ve had some wine to drink, and they don’t remember you the next day.

That’s right. What’s exciting about it is that when in the first iteration of festivals, virtual festivals, some festivals have just tried to copy exactly what they did as a physical festival. And that’s not really the possibility of being virtual. And with the canned market, which just happened, it was amazing how literal they were in duplicating the way the marchais was laid out with booze and the way that screenings were handled. And I guess that’s an okay way to begin, but once you do it once, then you’re going to say, “well, that really didn’t work so well just trying to translate from what it used to be.” So now, let’s figure out what we can do looking forward. And in the case of CPH:DOX, they’re interested in all the new opportunities that they can provide to filmmakers. And I’ll give you a couple of examples. So in a typical festival, if you have a film, you get a chance to introduce it if you’re in town that day, and maybe you got a few minutes to say some pro forma thing, and then you sit down. But in a virtual festival, you could have created a digital introduction, which could be more minutes, and could maybe talk a little bit about some of your other films, and why you were so passionate about making this one. So to be more substantive and give people a better sense of you as a passionate filmmaker. Okay, so let’s go and then go to the Q&A. So as you know, a typical hustle Q&A, 15 to 20 minutes, is really superficial, always getting asked the question of how much was your budget, and you don’t really learn that much. And as a filmmaker, you have a sense, there’s an audience out there, and hopefully, they liked your movie but beyond that, whatever. So imagine a situation where the Q&A’s are done in the Zoom mode, they’re way more interactive, and they can be longer, and the filmmaker is going to learn a lot more than they would in this kind of physical Q&A model. And then here’s another possibility, when somebody buys a ticket for a virtual festival, the festival could give them an opportunity to opt into the filmmakers’ mailing list or their social media. So that way, the filmmakers could build their personal audiences that they take with them throughout their careers. I think that would be really exciting. And here’s one more idea. So when you go to a big festival, let’s say Toronto or Sundance, and there’s a film that’s going to play and displays the director you’ve never heard of, and you look at the bio. And the bios are usually three sentences, and then it lists some other films that they’ve made previously, that you’ve never heard of and probably will never have a chance to see. But what if in a virtual festival, they have links to the previous films of that filmmaker, even if they’re not in distribution, they can work with the filmmakers and make them available through their servers. And that way, you could see somebody’s body of work that you were excited about. I think that would be amazing.

That would be. Everything’s changing, isn’t it? It’s moving fairly fast. Boy, that train is on the tracks.

Well, I used to say that things are changing every 20 minutes. I think now it’s every five minutes. But I think what that means is that people can be experimenting and exploring new models and not just stuck in the old model that’s been around for decades.

Well, nonlinear editing too, allows you to output just about any format so you can meet the requirements of any festival. I mean, some of them are even taking H264 formats now for the films. I would always worry about really good sound, though, I think that’s very important. But this is awesome. And we could get into the whole tech side. The geek in me is coming out. But they can contact any of these festivals and get the submission rules and find out exactly what format they need to submit it. And I think that the reason they could mount this in six days was that they had already gotten mostly digital submissions. And so they just rode the crest of that wave and turned it into something wonderful. I really have not had a lot of interaction with that festival, and I’m definitely going to look more into it. They sound like brilliant people.

It’s done by two amazing women. They took the risk, and they had the courage; they didn’t look back. The thing was a bigger success than the festivals ever been. And they can’t wait till next year when they can take all that they’ve learned and do better.

Now in terms of windows because the windows have greatly changed as well. Are the restrictions for which festivals you enter first now also being lifted, or do you have to go to Cannes first or Sundance, or does it matter? Are the festivals changing their rules?

The festivals like Sundance have been an announcement sort of about what would be happening, and Toronto has made a little bit of announcement. But they don’t even know if any, really, if physical screenings are going to be possible, they hope so. So in terms of the rules, I think you would assume that premieres would still be important. Sometimes those require world premieres or national premieres. Other festivals prefer them. So I think filmmakers need to be careful. But one thing people can do is do what I call secret screenings. So the True/False Film Festival has a way in which they’ll show a movie, they won’t announce it, they won’t be in any printed form, and only the people in the room know what it is. And then the premiere, they’ve held on to their premiere for Sapphire and Tribeca. And so that’s an approach that some people are taking. And another thing that filmmakers should understand is that this is particularly true for documentary filmmakers. You can screen your film at conferences, before you go to festivals, or before you premiere at a festival because those are considered private events. And where the public can come along and see a film. And so there are ways that you can show your film that isn’t going to interfere with a premiere. And I want to tell you an example of virtual screening. Can we talk about that for a minute?

Absolutely. Thank you.

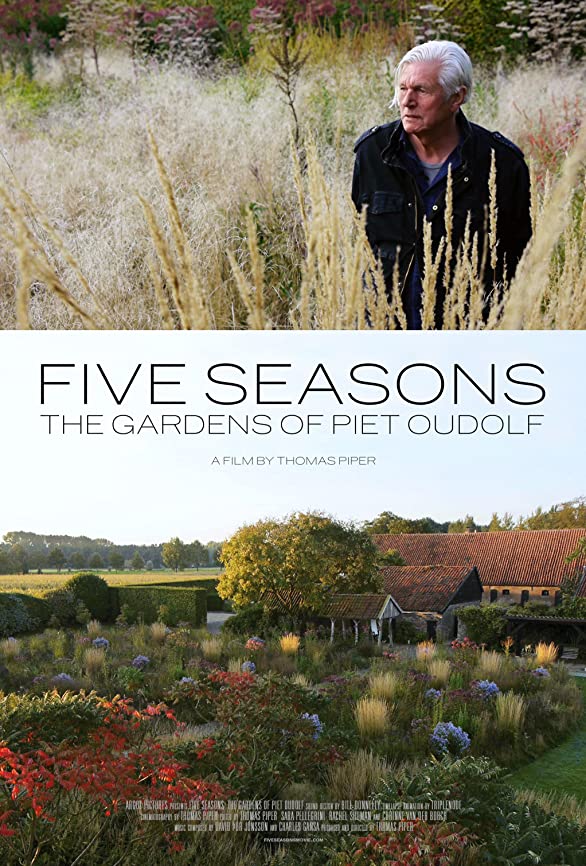

Okay. So this is a film close to my heart called Five Seasons, it’s a feature-length documentary about the world’s greatest garden designer. And I worked for a couple of years with the filmmaker. And then, early in April, he got an invitation to do a virtual screening where this company called Hauser & Wirth, which is an art gallery network. And so they wanted to make it available for free to people who got their newsletter, and they have galleries around the world, and they have a mailing list that goes to 50,000 people. So the weekend after Earth Day, late April, the movie was available for three days, 72 hours. And at that time, there were 1 million views globally. And 1 million views translates into probably 1.5 million people. Because a lot of the views are two people are watching it, or three people are watching it. So it’s 72 hours, and more people saw that movie than seeing most documentaries in their entire life cycle. And no distributor was required, the filmmaker just had a great partner that could make it accessible to an audience, and the audience came along, and then there was a lot of word of mouth. And in this situation, the movie is 75 minutes, and the average viewing time is 71 minutes. When you think about it, that means that, okay, most people didn’t watch the end credits. So most people watch all movies; they weren’t just checking it out for a minute, or two or five. So now, for this filmmaker, he got a fee to do it, but the screenings were free. But he’s now gotten lots of requests to do more screenings, which he can charge for. He’s expanded his mailing list by, I think, at least 2000 people. And there’s an exponential growth in the awareness of the film around the world, which is going to create all sorts of opportunities for him. So the idea of virtual screening, there’s a time, it could be two hours a day, three days, where you’re making your film available online. There are all sorts of opportunities there because you can charge if you have a partner organization that wants to do a fundraiser, you can use it as a fundraiser and charge more, and then split the revenue with the partner. It’s a way to build your relationship with these partners where they’re gonna support your movie further along the way. And going back to Windows, there’s a distinction between private virtual screening and virtual public screening. So, private virtual screening is only for people like members of one organization or people attending a virtual conference. It’s not open to the general public. So you could be doing private virtual screenings in almost any window and not interfering with the sort of traditional rights. So it’s kind of an amazing opportunity. And right now, in the middle of the pandemic, filmmakers are stymied because theaters are closed, festivals are in transition, etc. If they have a great partner that has a network that’s either national or global, they can make the film available to them. And that could be of huge value to the filmmaker in the career of the film.

How do you think this is going to affect a film’s ability to qualify for an Academy Award? You have to have New York and LA at least, right? In a theater?

Well, no. But this year, they said, the Academy has made an exception, and they said, it doesn’t have to be in the theater.

Okay.

Because they know how basically theatres are closed, so the restrictions have been loosened at least for one year. And then I would also say to filmmakers who are listening that it costs money. I mean, generally speaking, people spend about at least $20,000 qualifying a film if they’re going to be doing four-walling theatre in New York and LA and then doing some publicity. With documentaries, each year, I’d say 160 to 170 films qualify, and then the shortlist is 15 films. And being on a shortlist has never helped anybody’s career as far as I can tell, maybe one or two exceptions. So then you’re trying to get a nomination. There are five nominations each year. And I would say, most years, there are two or three films that are a shoo-in. But then it’s 160 films minus the shoo-in trying to get into two or three places. So the odds are extremely long, and if you spend the money and you don’t succeed, then the money’s gone. So a lot of times, there are ways that filmmakers can spend that money in a smarter way and get guaranteed results. So I don’t think that it should be an assumption that all films need to qualify because so few films managed to make it through the long odds.

What’s happened with aggregators in the last couple of years?

Well, it’s funny if anybody could really define that term.

It’s kind of a loaded question, actually.

Between an aggregator and distributor, no aggregators can call themselves distributors. I guess no distributor calls themselves an aggregator. But I guess the simple way to think of it is that a distributor is supposed to be responsible, or partially responsible for marketing a film. Whereas an aggregator doesn’t do any marketing or publicity. So their job is to really connect the film with distributors that are going to make it available. So filmmakers, I think, don’t always understand this. And so they’ll work with a company, and the company will put it on iTunes and Amazon and try for Netflix and Hulu, but they’re not promoting the movie to the public at all. They’re just trying to connect it to distributors. And that’s a real challenge because the filmmakers themselves, or distributors, or other partners have to be helping them publicize the film. So the aggregators are kind of in flux. I mean, the distributor went under, they were great for a while, and then they just kind of ran out of gas. And now filmmakers are worried because, and this is true for distributors and aggregators, a lot of those companies are not really paying on time or ever. And so, filmmakers worry that not only they’re not going to get paid, but then the company’s going to go out of business, and then what. So I think people need to do their due diligence whenever they get a distribution offer. And in my mind requires them or to talk to three to five filmmakers who are in business or have recently been in business for that company and find out what the real experience was. You don’t have to find out the exact numbers of how much money they’ve made. But you can find out if the distributors lived up to its promises, if they’re responsive, and if the filmmakers have actually received some money. So I encourage people to always do due diligence because no deals better than a bad deal. And then the second part of it is when they get a distribution agreement, the way it will work, if somebody is interested in your film, they’ll say, “Oh, we’ll send you the boilerplate agreement.” So translate boilerplate into the worst agreement that they could dream up in a million years. They’ll send you that, and they’ll say, “well, but we can negotiate it.” I think it’d be much better if they’d send you a fair agreement and you could negotiate that. But don’t assume that you can’t negotiate an agreement. Don’t be afraid if you only have one offer, that if you try to negotiate it for a fair deal, that they’re going to run screaming from the room. And a bird in the hand here is that” if I don’t take this deal, even though I don’t hear good things about this distributor, even though the deal doesn’t seem fair, I’ll never get another offer,” I think that’s a really bad way to look at things.

It costs money to submit to film festivals; maybe some of them will lower their prices since they don’t have the expenses of all of the live events. I’m hoping that will happen. But if a filmmaker is budgeting for obvious post-production, everything that goes into that, but also PR, marketing, travel, and submitting to festivals, can you give us a ballpark number? You have the kind of film as a documentary that festivals are going to like, how much money should you put in your budget for festivals?

First of all, a lot of festivals, if you ask, are willing either to lower or eliminate an entrance fee. So I think it makes sense to try that. And a lot of filmmakers I know have succeeded somewhere in between a third and a half of the time. The next thing is that if your film gets into a film festival, one of the first things you should ask is how much of a screening fee they can pay you. Sometimes what happens is the line kind of goes dead for a while, and then the person on the other end says, “Well, I’ll have to ask my boss,” well, that’s fine. I mean, if somebody else is getting a screening fee, then you should get a screening fee too. But if you don’t ask for it, they’re not going to offer it to you. So in terms of travel to festivals, I mean, in the short run, there’s not going to be a lot of traveling because we’ll be in virtual mode for a while.

From your kitchen to your garage.

Right. There you go. So I don’t know, I think that in those situations, you have to kind of evaluate each festival and say, is this a real opportunity? One thing is clear that if you have a film at a festival, and if you’re not there, it’s like the tree falling in the forest with no one to hear it. But on the other hand, there are a lot of festivals that are going to them isn’t going to really help you a lot, because it’s a smaller festival. It’s really more of a local event. So I think people have to be pragmatic and decide, well, these are the ones that are going to really make a difference. And then they allocate their limited resources to those.

Well, Peter, you are an amazing resource for documentary filmmakers. I know that after they listen to this, people are gonna wonder how to get in touch with you. How do they get in touch with you if they have something they want to submit, and what do you require of them?

Well, it’s really easy. My website is peterbroderick.com, and on the website, there’s a form that people can fill out if they’re interested in the possibility of me consulting with them. We call it the Filmmaker Form. And then once they fill that out, and I’ll look at all the forms and the films that I think I may be able to help and I’ll arrange to do a phone call with them. They don’t have to worry about coming too early because, in terms of the kind of work I do, there’s no such thing as too early, but there is too late. So early is good. It’d be great if there’s something to see visually so it could be a sample, a little clip, a teaser. It doesn’t have to be a whole film by any means. And then we kind of work from there. But in many cases, I’ll talk to filmmakers. And once I talk to them, and I’ll realize that there’s not a way I can be meaningfully helpful. But on the call, usually, I can give them some helpful advice, and those are all free calls.

This is a little off the subject, but I’m just thinking, is there any advice you can give people about the length? How long should these be?

Absolutely. So, in general, you don’t want your film to be more than 90 minutes or 86 minutes, which is the PVS hour and a half version. If your film is 86 minutes or less, then that’s a good thing. But even if you’ve made a feature-length film, I’m going to recommend that you also have a version that’s an hour, which would be somewhere in the 54 to 56 minutes range. And this may seem radical, and then I’d also like you to have a 15-minute version. And not a 15-minute trailer, a 15-minute version with content, you’re not trying to shrink the whole movie into 15 minutes, but you’re trying to take some content that is going to be really useful for people. And those versions all can travel in different lanes and support each other. So the ideal mode is 90 minutes, 86 minutes, 52 to 54 minutes and 56 minutes, and the 15-minute version. And I’d like you to make them all simultaneously not say okay, at some point we’re going to get to that. And each of them can be great and be used in different ways.

That is an amazing idea. I’ve never thought of doing all those versions at the same time. Hmm. Yeah, usually I’m dealing with a network clock or something like that, and they’re very specific about that, in my experience. So this is great.

In our version, PVS is 56-40. and international is generally 52 to 54 minutes. And that also will work for you for educational distribution, if you want to be able to be seen in a class period. So that’s a really good length. I know that of one filmmaker, she had a feature, and also had an hour version, and she goes around the country, and she’d be speaking. And when she showed the feature, no one stayed for discussion. When she showed the hour, almost everybody stayed. And that’s just a function of how time works in our lives these days. And recently, two of the films that I’ve been consulting on, they started out as features, and they made hours. And the hours are much better than the features because they just compress things and get to the essence of things, and they’re great.

Well, speaking of time, I could keep you on forever, but I want to be respectful of your time. I really, really appreciate you coming on again. These are some amazing answers. And I encourage everyone if you do have a documentary and you want to think about strategizing with someone who can really help you go to peterbroderick.com. Before we go, Peter, you are in the process of assembling a whole series of tutorials. Can you tell us where to go when they’re ready and when they’re coming out?

Well, in the short run, they can just go to peterbroderick.com, or you can just send me an email Peter@peterbroderick.com, and then I’ll get you all the information. It’s a virtual crash course. We’ll have ten sessions about the latest in distribution. And we’re very, very excited about it. The website for the course is called superchargeyourdistribution.com. So I encourage people to find out more about it.

Well, that’s wonderful. I’m looking forward to it. I’ve been speaking with Peter Broderick, distribution strategist, and someone who lives in the fast lane when it comes to documentaries and can give us a lot of information about how to maximize our films. After all, we’ve been working very, very hard in them for years. Let’s contact Peter and see what he can do to help us take them even further. Thanks for everything, Peter, and we’ll talk with you again very soon.

Thanks a lot, Cirina.

And everyone remember what I tell you get up off your chairs and go do something absolutely wonderful today. This is Cirina Catania saying bye for now.

Important Links:

- Peter Broderick

- Peter Broderick – Facebook

- Supercharge Your Distribution

- Paradigm Consulting

- Academy Award

- Amazon

- Berlinale

- Biennale Cinema 2020

- CPH DOX Dokumentarfilm festival 2020

- Edward Snowden

- Festival de Cannes

- Five Seasons: The Gardens of Piet Oudolf (2017) – Film

- Hauser & Wirth

- Hulu

- International Film Festival Rotterdam: IFFR

- iTunes

- Netflix

- Producers Guild of America

- Sapphire and Tribeca

- Shift72

- Skype

- Sundance Film Festival

- Toronto International Film Festival: TIFF

- Tribeca Film Festival

- Vimeo

- Zoom

Checklist

- Be ready to pivot during these uncertain times. The pandemic has forced a lot of change. It’s important to adapt to these shifts to keep going.

- Take advantage of virtual events. Since physical events are canceled, doing them online is the solution. Conferences can now become Zoom meetings and awards shows can be streamed live on the Internet.

- Choose a streaming service that has the capacity to air my film in its best quality and protect the copyright. Sites like Vimeo and Shift72 are recommended.

- Get a list of the press and industry personnel who took part in film festivals and events last year. This lets you research more about them before upcoming events.

- Be prepared for the Q&A portion of conferences. Run through the most common questions distributors ask and make sure you have a clear and concise answer for them to better get to know your project.

- Don’t be afraid to experiment and explore. Find new and innovative ways to present art through film. Keep the craft continuously evolving.

- Surround yourself with trusted partners and teammates. Use your talents to collaborate and produce something worthwhile.

- Keep growing your network. Get out there to gain more exposure. Join as many festivals as you can, promote your film, and always aim to create great relationships with your colleagues along the way.

- Always strategize your next move. Filmmaking is a business and with every step, make sure you’re gaining new experiences and increasing your finances.

- For more information on how to proceed with independent filmmaking, check out Peter’s website, www.peterbroderick.com.