“I shoot movies, brew beer, and ride my bike.”

Scott McLeslie, DIT, drone operator and cinematographer talks with host Cirina Catania about his recent work with Village Studios on some pretty awesome projects with major stars and a great team. He has some very interesting and amazingly candid comments about the future of the DIT’s position with the production—and it is NOT on the set! We grabbed Scott as he was in his car and stalked him at the airport in Nashville as he was headed out to his next assignment. Listen in!

In This Episode

- 00:14 – Cirina introduces Scott McLeslie, DIT, drone operator, and cinematographer.

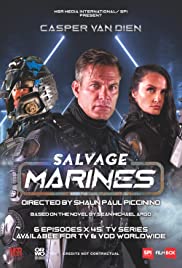

- 05:20 – Scott talks about the TV series Salvage Marines, directed by Shaun Paul Piccinino.

- 11:01 – Scott explains the intricate ways of shooting on RED Helium’s 8K camera when working on a movie.

- 16:56 – When did Scott McLeslie first realize he was born with creative skills that led him into the film industry?

- 21:53 – Scott discusses how they produce LUTs and color grade on sets using Qtake, a digital video assist software.

- 26:05 – Scott explains the seamless workflow he structured for Village Studios’s setup for making various productions.

- 31:17 – How is DIT going to be handled in the future?

- 36:27 – Do DITs need to be on set/gig all the time? What are the primary key responsibilities of a DIT?

- 41:57 – Scott talks about Grand Isle, a film directed by Stephen Campanelli.

- 48:16 – Visit Scott McLeslie’s website at scotty.ru or his company Black Hangar at blackhangarstudios.com to learn more about him.

Transcript

This is Cirina Catania OWC Radio, and I am so excited. Scott McLeslie is on the phone with me. We’ve been chasing around trying to get this interview done for at least a month now, but his production schedule is unbelievable. Scott, where are you, and what is happening today? Oh, by the way, I should tell people what you do so they have a little bit of background. Scott is the Chief Technical Officer at Village Studios and Black Hangar. He’s a DIT specializing in 3D stereo and 360 imagery engineering, and he’s also a post-production supervisor. And he’s been around for a while now, even though he’s quite young. So we have a lot to talk about today. And let’s start off by asking you where are you? Where are you going? What’s happening today for you?

All right. Hello, everybody. It’s super exciting to be on the show. And at the moment, I am traveling to New York. We just wrapped a shoot for the first block of Salvage Marines, which is a sci-fi movie that I was not only doing DIT, I was flying some drones, shooting some camera. And now I am off to do some establishing shots for our next thing.

Oh, my goodness. Are you in a car? You’re literally traveling. I mean, when you say you’re traveling, you’re literally in the car, right? Sounds like it.

Yeah, I am. Don’t worry, and I’m not behind the wheel, so it’s safe to talk.

Okay, good. No texting while you drive. I’m glad you’re not driving. That’s awesome. So you’re headed to the airport? Where are you currently?

New Orleans. We started off in Baton Rouge, and we are almost at the airport in New Orleans.

Oh, my goodness. Well, we’re just gonna keep asking you questions. So first of all, let’s just set a stage for what is Village Studios? What do they do, and who do they do it for?

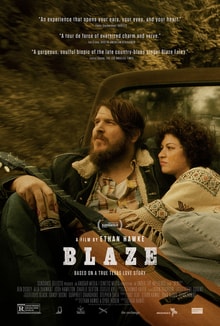

Okay, so Village Studios is a pretty interesting project in terms of its size and capacities, because the way it was built, it’s relatively new. The major renovations happened three years ago, so what we tried to do is we tried to take the top of the top technology, basically shrinking a full-size production studio into a very, very small footprint of the property, everything we need to run a full-scale production of tier two, tier three if we must. Should I say, we succeeded. The last productions we did though the Jeepers Creepers, Blaze, those movies you don’t actually shoot in the middle of nowhere, in a really tiny studio, yet we managed to do it. Village is an interesting high tech-way of seeing cinematography.

Village does a combination of soundtrack work, audio work, film work, television work, correct? I mean, it’s all over the board.

Yeah. It’s a studio that has a full cycle of production, starting from script works up to international delivery. The last feature we did, we delivered straight off the studio to theaters as DCP. So yes, it’s a one-stop-shop for anything you need.

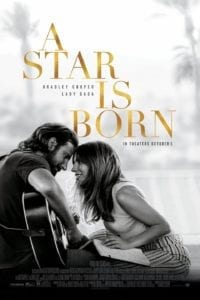

Well, I’m on the website, and I’m seeing pictures of Lady Gaga, and Bradley Cooper for A Star is Born. I’m seeing images of Willie Nelson. I can hear you getting out of your car; you’re at the airport. You are such a trooper to do this while you’re traveling. Thank you.

My pleasure.

Yeah, so this is amazing. You know, when you work in production, you just gotta seize the moment, don’t you? If we don’t do this now, we’re probably not going to have another chance. So tell us a little bit about Salvage Marines. When you get to New York, are you shooting some plates, or what are you doing for Salvage Marines?

New York is going to be a different gig. I am so obliged not to talk about it in terms of the details. But yes, this is going to be played shots from the drone, and there’s a special twist to it. That’s why I need to physically go there and do it myself.

Oh, my goodness, well, we’re gonna have to talk to you again. So let’s go back to Salvage Marines. What is that project, and what have you been doing on it?

That’s a really interesting sci-fi TV movie that’s going to be released probably sometime early next year. And this is really weird because of the way we set this project in terms of the budgets allocated to it. It was never going to actually happen. But purely juggling technology, we actually made it possible to squeeze this production into this kind of a budget. And when certain artistic decisions that we made, we took very old anamorphic lenses for those gigs, which is not the usual way to go if you’re trying to meet a short budget. But what we ended up with is an image that looks like tier-three production with all the glory of an anamorphic lens. That was basically shot by a tiny, tiny crew in a fraction of the time that you used to shoot such projects. And most importantly, that’s what’s possible because of the guide DI workflow that we implemented there. We had our editor working with the set, online, in real-time, so he was basically cutting as we went. There was like 5-10 minutes gap in between the camera stop recording and the editor actually getting the take. So before we broke down the set, we had a green light from the editor where we have all the shots we need, we have all the inserts we need right down the set. There were zero reshoots on this gig. And yeah, this is mostly done because the DI workflow allows us to produce editorial footage in real-time.

So this is season one. I just want to set the stage for people so they can keep this in the back of their minds because this is radio. We’re talking about season one, and where is this airing? Is this going to air on traditional television, or is this for Netflix? Where’s this going to be?

Last I checked, the distribution team was winking at me and saying that we should talk about that a little bit later. I think there is something big coming up with this, and I don’t know what it is, but they look super excited.

Knowing you guys, it’s gonna be something awesome. I’m looking on IMDb, and I see it starring Casper Van Dien, Armand Assante, and Elle LaMont, among others, and directed by Shaun Paul Piccinino.

Shaun Piccinino, a wonderful person to work with. He can energize the entire crew with his enthusiasm. I enjoyed working with him.

Well, he definitely looks like an alpha male judging from these pictures I’m looking at. How long did you work on Salvage Marines, and where was that shot?

Another interesting fact about Village Studios is we tried to do as much as possible either on the property or like 15 minutes away from it. So the entire thing was shot in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, right around where the studio is.

Oh, that’s great.

Yeah, they’re in some really exciting scenery with partially abandoned structures, factories in the background. So it’s really worked for us to depict planets for ecological situations. The picture looks really wonderful.

Oh, I can hardly wait, this is gonna be fun. So tell me again what your role was in that film. What different parts did you play?

That was really interesting because, in this specific movie, I mostly focused on camera works since the agility of my camera rig was pretty much needed there. So I stepped being camera B, action camera, but my team was doing all the DI. So I kind of supervise that since the main DIT on this gig was one of the graduates from my mentorship program that I run.

Oh, that’s awesome.

Yeah, I can tell you about it if you want. But basically, under my supervision, I had two of my team members grinding through DI workflow. And that was nothing easy because we shot those on RED Helium‘s full resolution. So that was about 10 to 20 with all the plates we did per day, 10-20 terabytes.

So you’re shooting 8K off the Helium?

Yep. And you cannot crop this down because you’ll crop the physical image. And since we committed to such an untrivial selection of lenses, we didn’t have that much of a range, so we could easily allow ourselves some cropping. So it was all shot to fewer than 8K. Nothing easy in there.

No latitude for error. You’ve got no room for error with shots like that. So you’re shooting on the Helium, who made the lenses that you were using?

Oh, actually, the lenses are amazing. It’s actually an ancient Russian lomo lens that was rehoused into new housing in China. So the lens itself just traveled the world one time just to get to us. And this lens is 40 years old. So it does bring oval the character, all the history of cinematography that it physically has through itself. You touch this lens, and you realize that something wonderful happened with this thing.

So how did you retrofit this to the Red camera? Did you have to take it to a special outfitter to have that lens? What happened there?

No, it’s a good question because those lenses, nobody likes them because they’re old and they’re tricky to work with. They breathe like hell. And I’m talking like certain specific lenses. You cannot focus right back in the shots. So with all those restrictions and limitations those old lenses bring, you have to kind of dance around them. But for the housing itself, it’s a PL mount, so it really fits. Except for the steel mounts, it’s just screwed on to a flat lens, once back. So it kind of plays as is. So throughout the gig, most of the lenses visited the bench at least twice. I had to realign them a little bit to keep working because just wear and tear throughout one gig kind of needs the lens to be serviced a little. So that’s why nobody works with them, but that’s where you get the authentic picture.

Oh my gosh, there’s so much history with those lenses, and there’s just something wonderful about stepping back in time. So I’m just curious about the production meeting when you were talking about the camera you wanted to use and the lenses you’re gonna use. What was that conversation like? Because this lens actually becomes a character in the film, doesn’t it? I mean, it has so much personality of its own. What went into the decision?

This lens is definitely is a character because committing to anamorphic, and your frame holds more information, so your creative side starts to think, what else can you populate this frame with? Yeah, the lens dictates how you will approach the picture, and the lens dictates the action in the shots. The lens dictates movement. It is a character, and this character has a character to it.

Oh, I can hardly wait to see this. Do you think you’re gonna keep using this lens throughout the series?

We basically walked it down to being the lens for this gig. It defines the picture, and we’re not jumping off it. It’s very hard to work with. And a 40-year-old lens in a sci-fi movie, it’s basically past meets future. So any action sci-fi movie, you have to have a lot of action, dynamic scenes in it, and the lens are super heavy, and dragging it on an Easyrig or on a Ronin is just purely painful.

Well, how much do you think it weighs? You think it weighs like 15 lbs or something, or is it heavier than that?

I am a metric person. The entire rig was about 39 kilos.

Oh, my goodness. Okay. Yeah, that’s back to 40 years ago.

Since I do have some experience flying stereo rigs back in the days, that’s kind of self familiar.

So you have to be strong to do that.

This is on the limits of basically gimbal capacities. I can do more, but the gear needs to catch up with me. So yeah, basically, it’s as big as it gets.

Wow. So you’ve got to be tired at the end of the day, right?

Tired, but happy. Cinematography is nothing and nothing of an easy job to do. But if we still do it, something does attract us to it. And for me, it’s excitement. It’s always excitement.

I want to step back a minute, and then we’re gonna come back to the workflow. But I’m very curious about you, and when you were a child. Where were you living, and when did you first realize that you were this wonderfully creative person? What did you like to do when you were five, seven years old?

I was really good at breaking stuff. Since I spent most of my childhood in Russia, there was not too much of an infrastructure to repair stuff I broke. So when my mom got her first computer, and obviously I broke it in 20 minutes, she told me that, “Okay, son, this is the reality, I have to do work, and this thing does not work. So whatever you must, go to a library, read a book or something, but this thing needs to get fixed.” I didn’t want to upset my mom. So I guess that was the first time I fixed the computer. Since then, the parts, how it works, have dominated over the parts, over any other aspects about a piece of technology. So definitely, when something new, like 3D or 360 imagery, pops up, I’m the first to jump in, and I’m the first to explore it.

So you’re definitely an adventurer, right?

Yeah, I totally like abusing technology and basically misusing it just to figure out if it works or not. Because this is how you invent, this is how you come up with something new. Take something that already exists and try to mix it together.

So you’ve got to have really fast drives to run all of this media. I mean, if you’re shooting between 10 and 20 terabytes a day, where is that going? And how are you managing that media? Talk to me about the DIT side of all of this.

Alright, so basically, for the last half a year, my magic wand would be ThunderBlade drive from OWC, which is just, should I say, ridiculously fast? And it made it possible. So I basically run a small distributed network for transcoding using a number of conventional machines to bring me some computing powers. Nobody’s using them at nighttime anyway. So basically, for the transcodes, I shouldn’t say steel, but I definitely rely on the computing power of every single machine we have in the studio. And I’m not talking just editorial machines with high processing power. I’m talking everything. I’m talking office machines, I’m talking about Mac minis, that we play our music in the bar with everything. And when it adds up, it’s really fast. But it always needs a fast hard drive to feed all these machines their chunks of data to transcode. And this is where OWC ThunderBlade comes into play. Because it’s a drive that is fast enough, not just for one machine but for four simultaneous streams, and this is the trick that actually allowed us to have a team of three people grinding through the entire footage, producing editorial material, and I’m not talking just the side stream that Red firmware. You can record a raw, and you can record progress, for example, for the editor straight on the camera. But it tripled the cameras and tripled the bandwidth of the cameras, so we could not allow ourselves that. It would cap our resolution, so we couldn’t go that way. So we have to physically transcode everything being synced with sound, and that’s what our editor got as they put us to work with.

Wow, okay, so you actually applied the LUT on the set?

We actually produced LUTs onsets according to the scene we’re shooting. Because during your normal shooting day, you’re jumping back and forth from one scene to another, and they’re not usually meant to become side by side. So you got to shift from place to place, and that’s basically how it goes. So you can’t just upload one LUT and call it a day. You have to constantly tweak change and do a full-on color grading on set. We use Qtake software. I think it comes from Slovakia and, basically, a tool to give you ultimate possibilities on set with video assist and everything you like, set wise. So basically, we grade with Qtake and live grade junction. And that goes and printed as metadata into every our R3Ds.

Can I ask you a naive question because I’m just wondering, is that non-destructive or is that actually baked in?

No, nothing is destructive with those workflows. Because the R3Ds and an initial set of metadata that the camera produces is basically read-only as soon as it gets off the sensor. The only place you can manipulate the data is only after two backup copies are produced, and all the checksums are checked and matched. This way, you can ensure that if you mess up something, at least you have another copy to restore from. As I like to joke with my students, one button that’s missing from the DITs keyboard is the delete button.

Yeah.

Anything even if it’s ridiculous and should be deleted, we can mark it for the deleted layer, but we never use the delete button on set, ever.

Yeah, sometimes it’s hard to know what’s in the director’s mind, too, as much as they’re good at communicating. There may be something that looks absolutely ridiculously wrong but fits somewhere in the final cut. You’re really smart about that. Can you walk me through a piece of media and take me through the workflow. You’ve got your scene, you’ve got your camera, the media goes into the camera, walk me through how it’s handled from there.

Let me break down this workflow for you super good. Okay, so it’s a Red camera that obviously exposes on a card, out of the cameras. And another lead goes to our onset of video Village card. It’s not even a card. It’s a Peli case on the C-stand, so you can take this thing with one hand, take the C-stand with another hand, and it’s super mobile, runs off the batteries, and it’s running done. So if you need a chase card to follow, fix your card. You can just toss that in and write immediately. You don’t need to rig anything, which adds a certain level of agility to the entire show. After that, that card has an Aja as a capture device for the computer that runs Qtake. And Qtake takes this image, encodes it into an H264 stream and distributes it on the local network to companion apps on iPads and iPhones and name it, and we have it for it. So everybody can see a live image off the camera wherever they are on set. It’s very important for dynamic lights for any close-up, for makeup and costume, so they don’t miss anything. We don’t need a crowd over one monitor, and usually with directors somewhere in it, not being able to make decisions just because it’s too loud. We don’t want any of that. So the director has his own iPad, everybody who needs to have their own iPads, and everybody is keeping their cool and keeping their quiet. On that station, there is an ability to regrade live image as well as any previously shot take. So you can go back to something you shot previously and applies a lot that you just created back to that previous clip. And the metadata will be followed up to the director and basically attached to this role file. So you will never lose this information. This information gets synced from Qtake metadata, basically, Qtake metadata is getting added up to R3D metadata upon the offload of the card. Obviously, all of those machines are connected to one network, and the machine that does the offload basically asks Qtake for metadata for the clips it’s currently holding. So everything gets synced automatically. And not just that, another copy of the footage is generated with the Qtake itself, with SDI feed that’s going off it by Qtake. It records a chosen formats, which for me is usually it’s pro revs since I’m a Final Cut guy, but our editorials are mostly Avid, so I do another one of the DNxHDs, and you don’t need a four for four of the Red SDIs since it does not deliver anything worth keeping in such a codec. But what it is, it’s four to two or even the program’s LTE just for convenience and speed to work with it. And DNxHDs are generated on the fly as yet another stream, and those go straight to the editor with the sound that’s coming off the mixing board that’s going actually back into the camera. So I have a proxy mix down of sounds synced to an R3D file just because this is another layer of protection against the errors that I do like to have on my workflow. Basically, if the timecode goes off, if the naming goes wrong, you still have that audio track, you can perfectly sync your footage to one another, just because it was embedded when you were exposing the card. So just another trick that would save me if everything else fails. After that, DNxHDs is a pretty wide codec; it gets uploaded to the cloud using a truncated device that holds five USB dongles connected to different cell phone services. So wherever I am, it gets me a pretty good bandwidth to the cloud. And that gets uploaded to the cloud, and the editor can start working with it as soon as it gets uploaded. And then, the entire workflow takes about five minutes to process any given footage.

So you’re working with proxies, and then you’ll marry it later. That reminds me of the old offline online.

Nothing actually happened since then because we used to have this as a digital intermediate. Now it’s the other way around. Now you have to have the same process but for proxies, just because your original media is too heavy and bulky to work with for the editor and for the rest of the team except the colorist. Nobody touches the raw footage but the colorist.

That’s perfect. So what NLE is he using? Is he using Final Cut?

Oh, it’s mostly Avid now. It’s mostly, but recently, and I’m a huge advocate for this, I like running everything on DaVinci, like the entire workflow on DaVinci. It usually takes an editor who is up for the challenge, just because it’s new, and nobody got used to it yet, but if you stick to DaVinci for NLE, for sound, for grading, and for delivery, oh, it’s fab. It cuts you at least two jobs overall from transcoding and conforms to one click of a button. After we’re done with the cut and we have an EDL, which is an edit decision list, which is a small XML file, a text file that basically says, go from the first second, second clip one and take everything to second number 10. Then go to clip two, from second, fourth, and second five, and it’s just a list of edits. With that conformed to the original footage, that’s the first place original footage comes into place. And that’s for colorists. So, yes, we’re working proxies.

How is DIT going to be handled in the future in your mind?

I’m pretty sure most of my colleagues will hate me for this, but I’m sorry, folks, we are not meant to be onset.

Okay, that’s pretty radical. How’s that gonna work?

Let me explain this. So I’ve been doing DIT for what? Almost ten years now? And throughout my career, I experienced so many different variations of how a DIT should be used on sets. There is never a standard. And what grinds my gears is there is never a project that utilizes the potential of a DIT one hundred percent. We either don’t know that we either never knew that this feature ever existed, or we just don’t have time for this or the DIT is not experienced enough to do all this in some realistic time framing. Because grading or editing on set takes not just understanding how you edit, it takes you a really unique approach because you have to do it in a hurry. You have to do it in the most uncomfortable space. And yes, the light will be bleeding on your monitor, and get a black t-shirt if you’re up for the challenge, stuff like that. But throughout summarizing all of that, I realized that the most important parts that DIT actually does for the gig are done on pre-production. Establishing the correct workflow that does work for the specific gigs, for the specific genre, and for the specific pacing production chose for the shoot is the most important task for a DIT. If you can build a workflow that is perfect, it will run on its own. You’re not needed there. Because what we’re confusing, and what everybody loves to confuse about DITs, there are two distinguished professions; there’s a data wrangler or data manager, and there is an actual DIT. Who does not offload cards, who does not sit and stare at silver stacks? He is a guide to understanding everything from the sensor being exposed with pictures to the delivery to the furthest theater in the world that’s featuring your movie. Unless this is not that, sorry, you’re not a DIT. And I’ve seen very little people with the entire knowledge for them to operate with. Because most of the time it’s not needed, we just don’t know about it. So my idea was instead of having a super-competent person trying to wrangle very heavy equipment through stuff–you know, there’s a running joke about deploying DIT, on different meme sites, because the card itself is just super bulky, and usually it stays in the camera truck just because you don’t need it on the set itself. Well, what do you know? If it stays in the camera truck, can I stay in an air-conditioned studio then? Because I’m not on set anyway. Like what do I have to solve to make that happen? Do I have to increase bandwidth from someplace to someplace? Or do I have to transcode it on site, so I don’t have to have big, huge bandwidth to actually push this footage on through the cloud? So it takes smart decisions on the start to basically automate the process while you go. I’m not saying a person with an understanding is not needed there at all. Well, if something breaks, you’re the first to be called. But for the normal general operations, this person is not needed. Like rating wise, seven out of ten gigs would either ask you to pre-grade the upcoming shots but still revert to 709 looks to put the lights properly. The only feature I witnessed color grading better on set actually benefiting the picture is where we shot a lot of night scenes, and we have to basically grade it to a dark night. And then DP was adding a little bit of flair lights. After the grading looking at the live picture, he added some additional supplemental lights were looking at the graded picture. He wouldn’t be able to see any of these if it was not graded to the darkest nights we can possibly have. So that was an advantage. We actually benefited from that. In most cases, when it goes against time, like okay, we will see this shot as it is right now, or give me 20 minutes, I’ll grade it for you. We don’t have 20 minutes. You can never imagine how much frustration it brings to a DIT that is there, that wants to do it, that knows how to do it, that’s almost done, but no, you can’t have those two minutes, sorry. And it’s understandable because those two minutes are needed elsewhere.

So you step back, and you run REC 709 on the monitors.

Yeah, not because there was something wrong with my grade, with my color, it’s just because the DP feels more comfortable looking at familiar 709 in terms of balancing out his lighting. And I understand. I would do the same. I would do the same because I can reference 709 off memory with a very deeply graded picture. I’ll have to go back and forth to the DP, asking what’s the highlights here? What’s with the shadows? Can we add here? Can we remove there? It’s a process. So for smaller gigs, DIT and data wrangler should be, not that their positions should be reconsidered, but their task list should be reconsidered. Maybe shrinking down a little, maybe utilizing a workflow that we didn’t discuss yet. But that’s something I’m working on right now, and it’s coming. It’s gonna be a hardware solution. I can tell you that right now.

I want to see this. You have to stay in touch with me. Are you okay on time? Because I know you’re at the airport, I don’t want you to miss your flight.

Yeah, I have a little bit more time. So we’re good.

Okay. Let’s just talk for a minute about Grand Isle. And I also want to ask you, you mentioned the ThunderBlades, which I think are one of the world’s greatest hard drives available now. They’re so so so fast and so reliable. Did you use ThunderBlades? You said you use them on Salvage Marines. What is Grand Isle? Talk to me for a moment about that project.

Grand Isle is our premium production that we did, starring Nick Cage. And Grand Isle is a place in Louisiana on the Gulf. And it’s a really deserted city. It works from season to season. In between seasons, it’s very empty. And the story is about, should I be talking about that? No, I shouldn’t be, not yet released, sorry. But what I totally can talk about is how we did the DI workflow there. And funny enough, the whole movie was shot in the studio and in the property right next to it, which is a wonderful Victorian mansion that the movie takes place in. But the actual Grand Isle, I was the only person to go to and get some drone coverage and some establishing shots. So yeah, I was the only one from the crew to actually see the place. We have three Reds working there on 6K, and we also use ThunderBlades because the workflow was pretty similar to Salvage Marines. It’s just my favorite thing. I tend to drag it from gig to gig. It just works for me; it works for everybody. So we have an online editor there as well. It was his first gig with us. So he was kind of wrapping his mind around his pacing. But in week one, we caught up, and since then, we were online all the time. So that’s really set up the thing.

So how were you using the ThunderBlades? What role did they play in the workflow?

They play the key role of being the first medium to receive the first offload of the card. So from that moment on, when it lands on the ThunderBlade, a certain process has happened to it. It gets transcoded to DNx, and it gets transcoded to H642 to go off the cloud. And the same ThunderBlade serves to be offloaded to an LPO because that’s another thing I’m using on set. Since you don’t need to touch Red raw footage, so with RAID, it’s a very good place to store it; LTO tapes.

Especially when you’re shooting 8K, you really need the space. That’s awesome. Well, the ThunderBlades, are you using the new generation that you can stack them? Because these are 4TB, I think, right?

Oh, yeah, I’m using the new generation that you can stack. And before I have some time with the previous generation, and I just 3D printed the stand for those. So yeah, definitely. Since they’re passive, and since they don’t have active cooling, they seek pretty well, and offsets and standoffs is a necessity with ThunderBlades.

Yeah, I think I need to let you catch your flight. But one question, you in the middle of all of this, you’re mentoring young people, how do you do that and how do you find the time and why?

That actually is an ongoing thing. I got ten graduates from my mentorship program, and it goes like this, I take a person from a film school, well, ideally graduate at a film school, and I bring him along. It feels like an internship program that you have on most gigs in the United States, but those guys get to bring your coffee, and those do not work with me. I want a person to be hands-on from day one, understanding that responsibility is something he cannot skip. So appearing onset as is, over the shouldering stuff I’m doing, helping, taking over, and it finishes off with the intern doing a gig of his own. Where I usually man some adjacent position just to see that he’s okay. Salvage Marines had one of my graduates taking over my twisted DI workflow and actually managing to keep up.

I think that’s a wonderful gift to the new generation. You’re just teaching really good business ethics too, and you’re providing something to them they don’t really get in a lot of internships. You’re right about that. A lot of internships just have them schlepping coffee and making copies. How much do you learn doing that?

I drink very hard to brew coffee, so I don’t ask for it. But as for working with actual footage that costs actual money? Yeah, that’s something that will inevitably happen to you, so why not starting like right now?

Yeah. Oh, Scott, thank you so much for taking the time. Where can people go on the internet to find out more about you, Village Studios, and your company, which is Black Hangar?

Yeah, it’s either blackhangarstudios.com. I have a small personal site that is scotty.ru, that I rarely update. But definitely, you can find my information there. If somebody wants to apply as my next intern, I’ll be happy to see the applications. So why not?

That’s awesome. So in order to do that, would they go to Black Hangar or to Village Studios?

They would go to Village Studios, that’s where I’m currently based at. I don’t know about my plans for London, but currently, I’m in Louisiana. And that’s where I operate from, and that’s where we are going to be studying as well.

This is great. And I want to thank OWC, not just for sponsoring this radio show but also for providing filmmakers like you with amazing equipment that they can use reliably on the set. So you have a wonderful, wonderful trip. Thanks for doing this. And when you can talk about this new project, let me know, and we’ll interview you again.

I would gladly come back to your show and talk about that as soon as possible. Thank you for having me.

Oh, that’s wonderful. Everyone, that was Scott McLeslie with Village Studios. I’m Cirina Catania and remember what I tell you, get up off your chair and go do something wonderful today. Thanks for listening, and thanks to OWC for sponsoring our show. Have a wonderful day.

Important Links

- Scott McLeslie

- Scott McLeslie – Facebook

- Scott McLeslie – LinkedIn

- The Village Studios

- Black Hangar Studios

- A Star Is Born (2018)

- Aja

- Armand Assante

- Arri PL

- Avid

- Blaze (2018 film)

- Bradley Cooper

- Casper Van Dien

- DaVinci Resolve

- DJI Ronin

- Easyrig

- Elle LaMont

- Final Cut

- Grand Isle (2019 film)

- iPads

- iPhones

- Jeepers Creepers

- Lady Gaga

- Mac minis

- Netflix

- OWC ThunderBlade

- Peli: Cases, Torches, Military, and Professional gear

- Qtake HD

- RED Helium

- Salvage Marines (TV Series)

- Shaun Paul Piccinino

Checklist

- Lay everything down during the production meeting. Discuss the storyline, equipment, timeline, and more. Most importantly, work with the budget.

- Minimize having to reshoot by carefully planning your shoot days. Consider factors like the weather, lighting, time of day, background noise, etc.

- Continue learning new filming styles and techniques. There’s a wide variety of cameras, lenses, lighting, and other film equipment available. It’s wise to know how most of the stuff works so you can add your flare to them.

- Learn how to improvise during filming. Sometimes the unexpected happens, and you need to be resourceful and quick-witted when the opportunity comes.

- Be particular in choosing the right lens for your setting. Sometimes the cinematography can be affected when the wrong lens was used in filming.

- Experiment with cinematography. Don’t just stick to one particular style. Since film is art, there is always the element of play.

- Keep quenching your thirst for adventure. There are millions of untold stories out there waiting to emerge and be shared around the world through compelling films. Go out there and capture them.

- Invest in good quality hard drives to make sure all your recorded scenes are in a safe, reliable place. Scott Mcleslie highly recommends OWC’s ThunderBlade Drive.

- Backup files but never delete them. Even if something seems ridiculous and should be deleted, just mark it as ‘delete later’ for you to refer to when everything is set and final.

- Check out Scott McLeslie’s website to learn more about his work and projects.