Seeing the Rocket Yard article about the model rocket launch at OWC Headquarters on July 16 commemorating the launch of Apollo 11 fifty years earlier set off a flurry of memories for me. It was in 1969 as a 12-year-old that I became obsessed with rockets big and small, which launched a lifetime fascination with technology, space, and writing. That hobby also led to a relationship with another budding nerd that still exists to this day.

I had been fascinated with space travel for years by 1969. I watched the Mercury and Gemini missions unfold, and by the time the Apollo missions began in 1968 I had memorized the lunar landing mission profile and used binoculars to learn lunar geology. I watched as the Apollo 7 crew worked out the bugs in the command and service modules, was amazed by the audacious Apollo 8 lunar orbit mission, saw the lunar module get tested on Apollo 9 and 10 (first in Earth orbit, then in lunar orbit), and followed the preparation for the first manned lunar landing — Apollo 11.

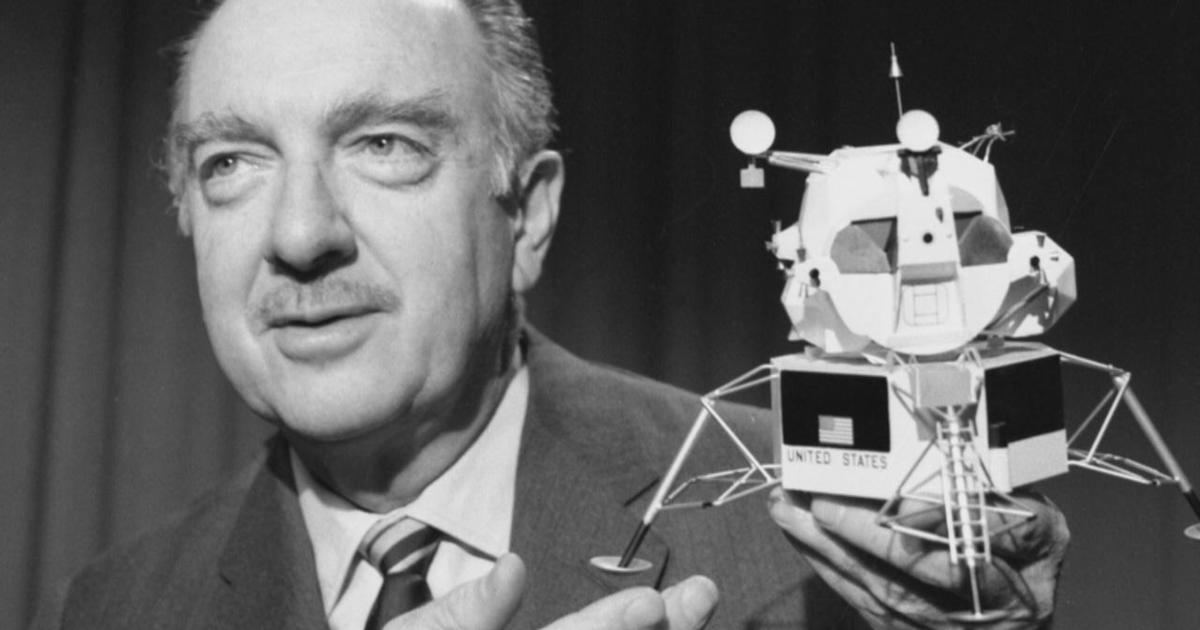

During the entire Apollo 11 flight, I was glued to the TV. Of course, we knew when the scheduled events were — the launch, translunar injection, the color TV broadcasts from the crew, lunar orbit insertion, and the landing. I remember the landing so vividly, sitting in front of our RCA color TV watching Walter Cronkite (see image above) and listening to the voices of Armstrong and Aldrin as they got perilously close to running out of fuel before landing. Watching Cronkite wiping a tear from his eye when the landing was announced with the words “Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed” was enough to get all of us who were watching teary-eyed as well.

After the landing (which happened at 1:17 PM MDT) and watching some of the coverage, I recall walking outside and thinking about what had just happened — humans were on the moon! Later that evening — 7:56 PM MDT — our entire family was gathered around the TV watching the first moon walk. Those ghostly black and white images (see image above) were enthralling and my mother kept repeating “I can’t believe it!”. We, like the rest of the world, were all relieved when the crew returned safely to Earth and made it through their quarantine with no issues. Of course, there were five more successful Apollo moon landings to follow as well as the Apollo 13 near disaster, but this was the one that sticks in my mind the most.

As transfixed as I was by what NASA was doing, I didn’t really pay attention to model rocketry until after the Apollo 11 moon landing. As I was walking home from school one day in September of 1969, I saw several ninth-graders launching a rocket, so I went over and watched. Not long after that, my family took a short vacation trip to New Mexico, and while I was in a store in Santa Fe I saw model rocket kits and grabbed an Estes model rocket catalog. That was it; I was hooked.

Shortly after that, I bought my first rocket kit; the Estes “Alpha” (see image below), which was a basic paper and balsa wood rocket for beginners. For years after that time (up until 1984 or so), I was building larger and more complicated rockets.

Photo: Model Rocket Building

The fascination with model rocketry got me interested in competition. I found out about the National Association of Rocketry, became a member, started a local chapter, and (with the help of a mimeograph machine at our school) wrote, edited and printed a newsletter for the group. We ran competitions in the state of Colorado, and I got to be friends with a lot of like-minded teens and adults through the NAR competitions.

Through the NAR newsletter, I heard about a company in Albuquerque, New Mexico that was building electronic payload kits for rockets. Micro Instrumentation and Telemetry Systems had several kits for sale, including a transmitter that one could use to send data on acceleration, temperature, spin rate, and so on back to the ground. They also made a kit that I purchased, which was an electronic flasher that went into a clear plastic payload section on a model rocket — if you launched at night and took a long exposure picture from a known distance away, you could actually figure out (from the precise duration of the flashes and the pauses between them) the acceleration, velocity and altitude reached by the rocket.

The connection between model rockets, math and physics quickly gelled in my mind. Before long, I was doing iterative calculations to estimate how high my rockets would go. Using crude theodolites and trigonometry to figure out the maximum altitude reached by my rockets, I was able to then correct my estimates of drag coefficients and make even more accurate altitude and speed predictions. Those rockets took a kid who had a dislike of math and turned him into a fan of algebra and the basics of calculus.

Like any male teenager of the time, I began to also notice members of the opposite sex. I wasn’t just interested in rockets — I liked to sing, so I took part in our high school choir and in musicals that the school district did during the summers. It was during one of those summer musicals that I struck up a conversation with the girl who was the accompanist for our show. She mentioned that she was going to start college in the fall of 1973 as an engineer, which really fascinated me because I had decided on engineering as a path. A girl who wanted to be an engineer? That was very rare in those days, and despite decades of encouraging young women to consider STEM careers, it is still rare!

I had another year of high school left, but stayed in touch with that girl – Barbara Mackinder. When I finally graduated from high school in 1974, we did another summer show together and became better friends. I started engineering school in the fall of 1974 and would occasionally run into her on campus while I struggled through my freshman year of a civil engineering curriculum at the University of Colorado in Boulder.

During this time, there wasn’t a lot going on in the American manned space program. The Space Shuttle was still under development, the Skylab missions flew by, and the singularly unexciting Apollo-Soyuz Project proved that Americans and Soviets could work together in space. When I ran into Barb on campus, we’d talk about what NASA was doing and wondered about the future of manned space. It was in the fall of 1975 that a mutual friend of ours was killed in a car accident and the two of us were asked to perform at a memorial service. Barb played the piano, I sang, and afterward spent a few hours just talking. We started spending more time together at that point.

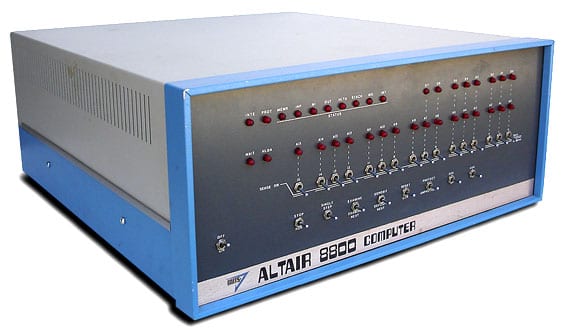

Now my connection with model rocketry was going to affect my life in one other way. Remember that company that made the rocket telemetry equipment? Well, in January of 1975 that company (MITS) announced the first personal computer kit: the Altair 8800 (see image above). A friend of mine who had more money than this poor college student bought one of the kits, and I helped him solder it together. It wasn’t too impressive until about a year or two later when it had a keyboard, a monitor, and a way to load programs into it from paper tape, but at the time it was my first exposure to personal computing.

Barb graduated from college in 1977 and went to work for a local electric and gas utility company, mainly because most aerospace companies were mired in the economic downturn of the time. Apollo was finished, and there didn’t seem to be much on the space horizon. When I graduated a year later in 1978, I also went to work for that same company. In June of 1979, Barb and I were married.

We still occasionally went to rocket competitions, we both had telescopes and loved to find deep sky objects, and were voracious readers of science fiction. In late 1980, Barb heard that local aerospace company Martin Marietta (now Lockheed Martin) was hiring, so in early 1981 she took a new job working for the company on the Titan launch vehicle program.

That career lasted through 2017, when she retired from the company. During those years, she participated in dozens of launches, including being on the launch team for her personal favorite — the Cassini/Huygens mission that spent 13 years orbiting Saturn and sending back glorious photos and important data. She also became a fixture on the conference circuit, having developed statistical methods of analyzing data and using it to improve mission success. Her paper on “Avoidance of Unverified Failures” at the 19th Aerospace Testing Seminar won her the prestigious Otto Hamberg award, presented to her at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL).

What was I doing during this time? Turning from a career in pipeline engineering and becoming an IT manager. I had purchased my first personal computer (a Commodore 64) in 1982, then quickly upgraded to an early PC clone (a Sanyo MBC-555). A chance assignment by a VP at the company I was working for had me develop a plan to integrate personal computers into our workspace, since I was about the only person in the engineering staff who knew anything about personal computers.

Flash forward to 1984, when I saw my first Macintosh. I fell in love with the quirky little machine, but I thought the first 128K model was too expensive and extremely underpowered. Later that year, the 512K arrived and I made the plunge. I won’t go into the details, but bringing that machine to work ended up influencing the choice of computers at our business; by the time the company was merged into its parent company in 1994, we had nearly 300 Macs in our little subsidiary and almost 1300 in the whole corporation.

Between 1986 and 1994, I ran a popular Mac-based bulletin board system (BBS) for a Denver-area Mac user group that is still thriving today — MacinTech. In the early 1990s I bought a book by TidBITS editor Adam Engst that started my wanderings on the Internet and by 1994 I had my first website up and running — a site about “pen-based handheld computers” called pdantic.com (link to an archive of the site on the Internet Archive Wayback Machine).

Due to an outsourcing in 1995, my employer became IBM while I was still working on IT for the utility company. I spent about nine years in various roles for the company, and sadly my first project was converting those 1300 Macs to Windows 95 PCs. That was also the year that I built the first website for that utility since I was one of the first IBMers who had actual hands-on Internet experience.

By 2004 I had tired of the pressure of being an IBM project manager and started my own company. My writing skills, which I had honed early on while creating that model rocket newsletter, came into use as I wrote a series of books for multiple publishers. While making a living as a Mac consultant and business analysis instructor, I spent my evenings writing. Eventually that led to a gig with The Unofficial Apple Weblog (TUAW.com), which was one of the leading Apple websites until it was absorbed into Engadget in 2015.

Photo by Steve Sande

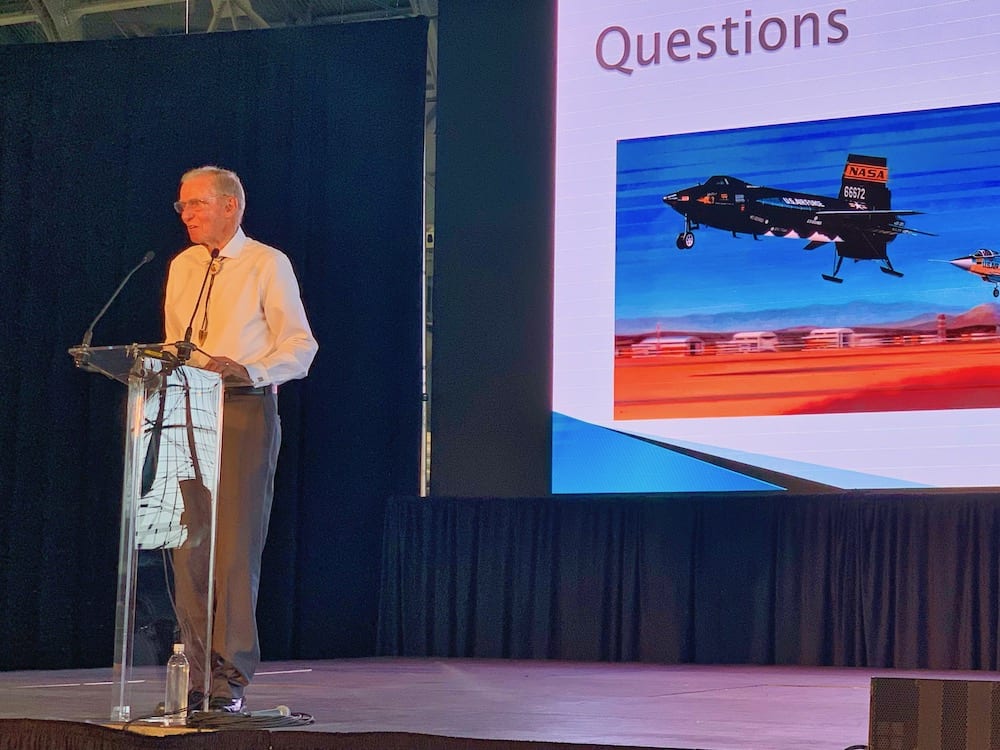

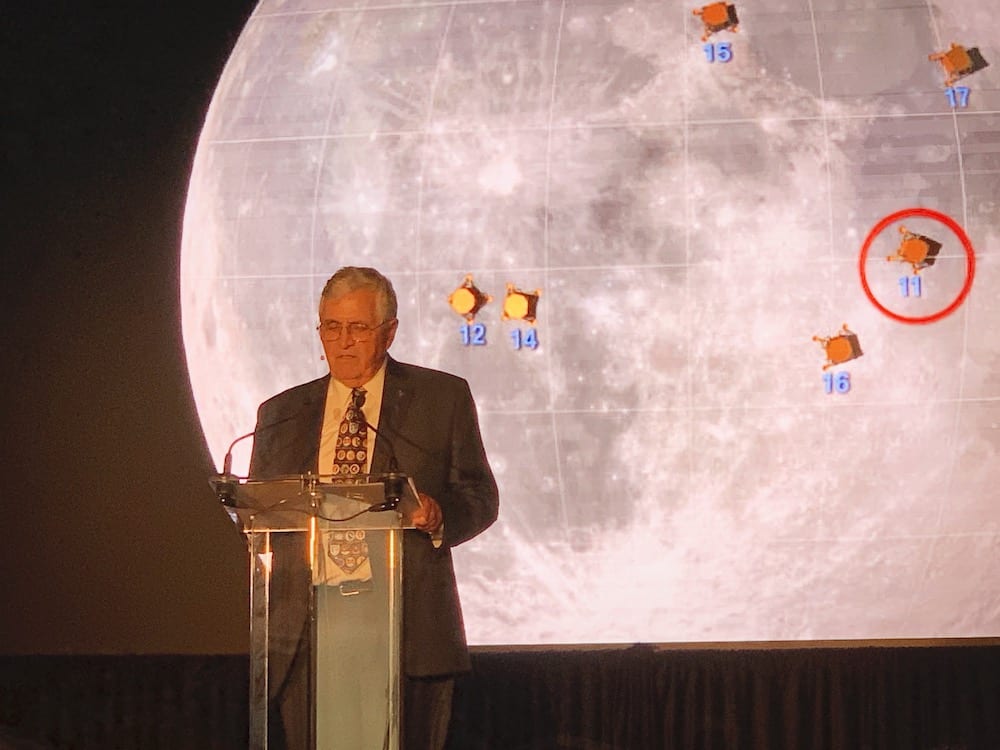

That leads full circle back to The Rocket Yard, as I was able to land a gig here that same year. Here in 2019, I just celebrated my 40th anniversary with my rocket scientist wife, and we’re attending a lot of this week’s “Apollopalooza” events at the Wings Over The Rockies Museum — perhaps the only air and space museum to spend a full week commemorating the first moon landing. We had the opportunity to see presentations by X-15 and Space Shuttle astronaut Joe Engle (see image above) and Apollo 17 moonwalker (and former US Senator) Harrison Schmitt last Saturday, and we’ll be watching the moonwalk reruns at the time they actually happened at an event on the evening of July 20.

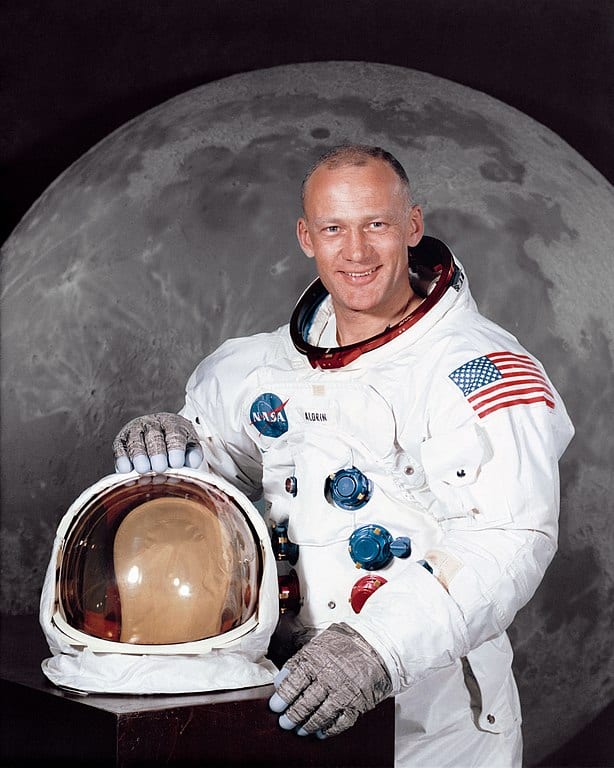

As I near the end this long autobiographical journey, I thought it was very appropriate to mention that three of our favorite pastimes — cruising, space and astronomy — collided in February of 1998 on a cruise to view a total solar eclipse in the Caribbean. A guest speaker on board that ship was none other than Apollo 11’s Buzz Aldrin. One night early in the cruise just after dinner, my rocketeer wife and I went up to Col. Aldrin and she asked him a question that he apparently didn’t hear too often – “What was is like to fly on a Titan II during your Gemini 12 mission?”.

Well, we spent the next two hours chatting with Buzz, all because of that one question. I had recently read his science fiction collaboration with John Barnes (Encounter with Tiber), so discussing some of the concepts in that book made for great discussion. Aldrin is also known for his pioneering work on manned orbital rendezvous and orbital mechanics, which led to a long discussion of the Aldrin cycler, a spacecraft trajectory that makes Mars travel faster, more efficient, and repeatable. That one evening in 1998 was an incredible experience.

Public domain image courtesy of NASA.

Fifty years after A

For our older readers who also watched the first Apollo landing and reveled in the experience on July 20, 1969, we’d love to hear some of your reminiscences as well in the comments section.

P.S.: I thought #ChasingTheMoonPBS did a good job of tracing the history of the moon program. It mentioned some social issues that weren’t given much publicity 50 years ago, such as the failure of NASA to promote (black) pilot Edward Dwight to astronaut status. There was a lot of color footage of events involving the astronauts and their families.

Ed – you want to hear something odd? I met Ed Dwight through my father in law — in fact, he was at the wedding reception for my wife and I when we got married. He was a fascinating man, an excellent pilot, and I hadn’t thought about him in years until you mentioned the PBS series.

Did you get a chance to see the Apollo 11 documentary that came out earlier this year? It is one of the best documentaries I’ve ever seen, simply because there’s no narrator – all of the narration comes from mission control, the astronauts, flight controllers, etc…

Steve

My first job out of school was signing on with North American Aviation (later Rockwell) in Downey CA. I had developed a relationship with NAA while working summers in the mid-1960s on the large welders which were used to construct titanium wing parts for the XB-70 supersonic aircraft. NAA was a primary contractor with NASA for both the Apollo and Shuttle programs. Signing on in 1968, I missed the sadness and scandal associated with the deaths of Grissom/Chaffee/White in Apollo 1, esp. the tales of careless construction, typified by the tale of the loose wrench found in the burned capsule. It was fun developing early computer models demonstrating how the CM+SM power & cooling systems could meet the mission requirements, and later on, doing computer modeling/design on the Shuttle power and hydraulic systems. Each Apollo mission was exciting, but it became clear by 1972 that the bust-boom cycle of the aerospace business was not to my liking! I had moved completely away from aerospace by 1975.

The night of the landing I watched it in my Dad’s hospital room. He was in ICU after a kidney stone operation that day. He was not doing well at all. I just can’t remember anything about the landing and the space walk.

I was asleep on the floor when at midnight a nurse can in and told me that my Dad asked for me. I rushed to his bedside, and took his hand. He didn’t open his eyes, but asked, “Did they land?” I replied that they did and both walked on the moon. He fell back into his deep sleep. I walked out of the ICU worrying if he was going to make it that night and went home.

By the time the Apollo 11 crew landed, My Dad was walking into our apartment.

He passed away last year in March. Glad that he lived to see men on the moon and the Chicago Cubs win a World Series!

Domingo –

That is a great memory, and thank you for sharing it! I think of the two major experiences your Dad lived through, the Cubs winning a World Series was much more unlikely than a manned lunar landing! :-)

Steve

Steve,

Thanks so much for sharing your wonderful life story. You certainly have had a life full of blessings. My life with computers also started with the Altair 8800. I think I hold the record for taking the first personal computer on a submarine mission. I was a nuclear submarine officer assigned responsibility for the combat systems department containing a central computer on the second submarine to have a central computer! I amazed the other guys on the mission with StarTrek on the Altair (after hand loading the boot code to suck in Microsoft Basic.)

Thanks again for your blog. I love to read it daily. Retired from 25 years at HP, after 13 years in the Navy, I now make extra bucks writing Mac programs for a customer on my iMacs suitably beefed up with Macsales SSD, memory and Thunderbolt dock. Keep those tips comin’. I always learn new things from you.

Rick –

Wasn’t that hand-loading the Altair by flipping the switches a pain? My friend was so happy and proud when he finally got a paper tape reader and a pirated copy of Microsoft Basic. That same friend went on to be a chip designer for Motorola and Freescale! Thanks for the nice comments and for your memories of the Altair.

Steve

Steve,

Reread this article again today. So glad the link popped up on a list of articles I had marked for new notifications. The nice thing about growing older was that most of the post was completely new to me!!! :-)

Keep up the great work and don’t forget the many of us who still have Intel iMacs and won’t be able to afford an M1 iMac until MacSales has used ones to sell.

Buzz Aldrin’s mother’s maiden name was Marion Moon.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Buzz_Aldrin#Early_life

David – Isn’t that an amazing coincidence? Aldrin was so nice to us when we approached him on that cruise, and we were surprised when he wanted to have a long conversation with us. I sure wish the iPhone would have been around in those days so we could have grabbed some selfies!

Steve

Thank you Steve for a lovely story with fascinating reminiscences.

My wife & I watched the first Moon Walk whilst living in Student Housing at Cornell on an old B&W TV. An unforgettable moment!

John – we were really quite lucky to be living when humanity took that first step. Let’s hope today’s college students get to live on the moon or Mars!

Steve