To some filmmakers, it’s a joke. For others, it makes their blood boil. And for some, when they hear it, their eyes practically roll right out of their heads. It’s the term “Fix it in Post,” and if you’ve been in the film and video industry for even a few months, at some point you’ve probably heard it used.

Today we continue part 2 of a 3-part series on what I believe is the ultimate guide to when you should and should NOT fix it in post. In part 1 we had fun with a philosophical exploration of what it means to “fix it in post on purpose.” Today we’ll tackle the more traditional way people think of this term–when something unexpected or unfortunate happens on set requiring a need to fix something.

A legitimate problem

Having done some form of video production for over two decades, and having interviewed so many filmmakers over the years, or written about filmmaking for so long, I have plenty of opinions on this issue based on practical experience. Nonetheless, I knew it would be worthwhile to reach out to their professional online communities.

One that I frequently visit and read is the Blue Collar Post Collective Facebook group. As of this writing, it has nearly 16,000 members from all over the world in every aspect of post-production. I was pretty confident that responses to a Facebook post like this would be popular. And I wasn’t disappointed. Within 10 or 15 minutes there were already over two dozen responses.

One editor who responded to my request (and asked to remain anonymous) shared this with me privately in a DM:

I think an even bigger problem than fixing problems that could have been figured out in pre-production is ever growing faster turnarounds. So many times, these corporations want high- quality videos but an insane turnaround. Again it’s not just lack of planning but also disregard to what burden this puts on an editor. Partly it’s because some of the producers are not real producers and are more middle management project managers who have little or no experience in filmmaking pipelines. So they over promise and expect the production and especially the post-production to do the leg work creatively. They just don’t give a f*** too. Editors get the brunt of the anger from producers because that’s the last step in the pipeline. Everyone passes the buck until they can’t pass it any more, and we’re stuck with all the problems no one cared to monitor. So that leaves some poor bastard staying up for days, sleeping near their desk, if they get any sleep, just to make a deadline that half the time, in my experience, could have been avoided or pushed back if any thought in pitching the project went into it.

That’s what “Fix it in Post” means to me. F*** you, I’m not going to do my job and properly plan how to do this to reduce what we have to fix in post (there’s always justifiably somethings that will need to be fixed). Oh and don’t complain either or I’ll take my business elsewhere and ruin your reputation “. Fix it in post is a big f*** you.

As you can read, this is something that really strikes a nerve with the pro post-production community. This person took the time to DM me privately and share this story. His full message was easily three times longer than this. Think about that for a minute. He’s not getting paid to write to me. He doesn’t want exposure. He just feels so strongly about it, that he took the time on a Sunday afternoon to write what itself could be its own mini-blog post.

Anything that has that much of an impact and affect on an industry is worth diving deeper into and sussing out the meaning.

Jamie Kirkpatrick, the editor on John Lequizamo’s indie film “Critical Thinking,” shared this story with me:

While we have gotten to the point, at least technically, where most things CAN be fixed in post, most of those fixes require additional spending. I can’t tell you how often I have reached out to a director during production to urge them to pick something up or redo something correctly, knowing that the cost to fix it in post will be an order of magnitude higher than if they just get it on set. A perfect example of this was on a film in which the main character is sitting on a partial set which would later be extended digitally. However when I got the dailies, there was an extra crossing through the shot. I called the director on set to point out that this would make the VFX shot significantly more difficult because the crossing extra would need to be rotoscoped. I asked if they could reshoot a take without the crossing extra and was told they didn’t have time and that “the VFX people can handle it.” Well, the VFX people were glad to handle it – at twice the original bid price. Needless to say, the producers were not happy about this.

Clearly this is an example of a situation where a little extra work on production could have saved a significant amount of time and money in post. So that begs three questions:

- What kinds of legitimate issues should you avoid?

- What can you do ahead of time to lower the risk?

- And how do you best determine a course of action when they happen?

“Be afraid. Be very afraid.”

There are certain lines from movies that just somehow tend to transcend their cinematic birthplace and enter the general lexicon. This quote from 1986s “The Fly” starring Geena Davis and Jeff Goldblum (who’s pretty much played some form of the squirrely Seth Brundle since then), is one such quote.

I use it here to serve as a warning from the kinds of situations you should attempt to avoid encountering whilst on set. This is of course not an exhaustive list. But I think it covers 90% of the situations you may find yourself in where “fixing in post” may be impossible or impractical.

Poor Audio

If I’ve said it once, I’ve said it a thousand times—every video producer and filmmaker worth his/her/their weight in salt will tell you that fixing poor audio is significantly harder than dealing with bad video. If you have a bad shot with less than ideal visuals, sometimes something as simple as b-roll to cover it is all you need.

But if you’ve recorded audio that is clipping because it is too loud, there is very little that can be done. Or, if another loud noise occurs during a shoot, there typically is no way to remove the unwanted sound without also removing the part of the audio you do want.

Did a mile-long locomotive blowing its whistle in the distance obliterate that amazing and emotional monologue from your main character? You better hope she can re-do it perfectly in ADR. Did a 747 fly over just as that super busy CEO who only has five minutes of his time to give you FINALLY got the sound bite right you’ve been attempting to record for that past 4 minutes and 34 seconds? Tough luck. Maybe in three week’s time, he can give you another 5 minutes.

The lesson learned: make sure your audio is as pristine as possible.

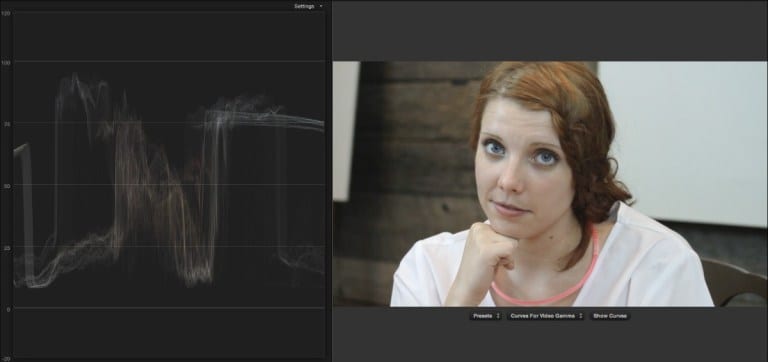

Poor Exposure

The visual equivalent of audio clipping is blowing out your highlights (which, actually, is also called clipping.). This is a case where parts (or most) of your shot sends the IRE scale to the moon, i.e. above 100 on the 0 to 100 scale.

An IRE value of 100 is typically pure white, and anything above that obliterates any details. All visual information is lost. (With HDR you can attain what’s called “super whites” that still have information and detail even above 100 IRE. But it’s still not ideal.)

Naturally, on the other end of the spectrum is a shot that’s too dark. Typically this causes visual noise, which although “fixable,” requires expensive software and very skilled artists. Today’s digital cinema cameras are so light-sensitive that even low-light scenes can look beautiful, but that’s still no excuse to have a poorly lit shot if you can avoid it.

Lesson: if there is no information in your shot, there’s literally nothing to “fix” in post. Make sure your shots are lit properly.

Out of Focus

Not unlike clipping audio or highlights, a shot that is out of focus is usually not something you can fix. Sure, you can throw a Sharpness filter on a shot, and if the focus is just slightly off, that may help a bit. But when paired with shots that aren’t out of focus, the ones with the Sharpness filter will tend to stand out. And it goes without saying, anything completely out of focus is unusable. (Admittedly, I cannot think of a situation where a shot would be that horribly out of focus, but I’ve been doing this long enough to know nothing is completely out of the realm of possibility.)

Lesson: this seems almost silly to say, but make sure your shot is in focus. Use tools like “Peaking,” wide angle lenses, proper lightning., experienced focus pullers, etc.

Unwanted items in the shot

Very few people, whether or not they’re in “the biz,” didn’t hear about the infamous Starbucks cup that made its way onto the set, the shot, and even the original broadcast of the HBO hit “Game of Thrones,” S8E4 “The Last of the Starks.”

The cup was eventually rotoscoped out of the shot for future airings, but I’m sure it cost a pretty penny. I also have no doubt HBO could handily afford it. But the question is, can you? Think about the example I gave above. You don’t want to be put in a position where the “fix” in post is tens of hours of VFX work.

Lesson: utilize crew members like script supervisors and ADs to ensure everything that’s supposed to be in the shot is, and things that shouldn’t, aren’t. Use playback devices to make sure all is what it’s supposed to be. And if you do see an extraneous coffee cup in your medieval world setting, take a do-over.

“Be Prepared”

In Disney’s “The Lion King,” the villain Scar sings the song “Be Prepared” and it could be a rallying cry for productions everywhere. The undisputed leading “solution” to the “fix it in post’ mindset is the counter—“Fix it in pre.” That is, dot all the proverbial “T’s” and cross all your proverbial “I’s” when in the pre-production phase of any production.

- Be aware of all potential sound problems and plan accordingly (e.g. train and plane schedules, turning off loud appliances and A/C units, etc.)

- Use the best possible camera, audio, and stabilizing equipment your budget can afford

- Hire the best sound and visual crew you can afford (e.g. DP, grips, audio engineer, script supervisor, etc.)

- Plan and rehearse scenes and shots so that come production day, the chances for errors are minimized

- Work with a competent producer (or producing team) with experience in the kind of shoot you’re undertaking

The best kind of preparation comes with experience. Something unexpected happens the first time, and then the next time you know what to do to prevent it from happening again (or at least significantly reduce the chance). But even the best-laid plans can be met with mishaps or misfortune. When that happens, someone needs to “make the call” as to whether or not to fix it in post. We’ll cover that topic in the next and final installment of the series, as well as offer a whole new perspective on the term. Stay tuned.