Lij Shaw speaks with OWC RADiO producer and host, Cirina Catania. He shares a bit about his Grammy awarded recording studio, The Toy Box Studio in Nashville. And if that isn’t enough, we also get a chance to hear about his yearly adventures with Hay Bale Studio at Bonnaroo, and his sessions with some of the world’s greatest musicians! They also discuss how Lij relies on OWC gear for his workflow and he shares detailed insight on its everyday use.

In This Episode

- 00:17 – Cirina introduces Lij Shaw, a chart-breaking, award-winning music and podcast producer and the host of the podcast, Recording Studio Rockstars. Lij is also the owner of the Grammy awarded The Toy Box Studio in East Nashville, TN.

- 07:03 – Lij describes the work that goes into doing a full studio setup for their Bonnaroo recording studio.

- 15:32 – Lij expresses how he prefers to mix while the band performs rather than doing a lot of work in post-production.

- 21:56 – Lij talks about his podcast, Recording Studio Rockstars, and the gears he uses for interviews and production.

- 27:33 – Lij tells the story of how he bought a vintage MCI board console that was supposedly inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame to put on display.

- 36:17 – Cirina and Lij discuss how OWC equipment helps them with their heavy workflow using storage and machine reliability.

- 43:40 – Lij tells how he quit his two jobs in London and left to join his brother’s band in Hong Kong.

- 50:16 – Cirina asks Lij how he handled shifting from analog to digital recording and the differences between the two.

- 56:06 – Lij shares some of the memorable moments he’s had with musicians throughout his music industry career.

- 63:40 – Visit Lij Shaw’s website, Toy Box Studio at toyboxstudio.com, and listen to his podcast, Recording Studio Rockstars, at recordingstudiorockstars.com.

Transcript

This is Cirina Catania with OWC Radio. I have Lij Shaw on the line. I cannot tell you how many awards this man has won, how many groundbreaking music projects he’s been involved with. And I have been doing some research also in prep for this interview. T here’s just so much. Lij, welcome. I’ve been reading about you, been listening to some of your work, and you have an amazing history. So how are you? What’s going on today?

I’m doing good. It’s a pleasure to be here, Cirina. And today, I don’t know what date this airs, but in Nashville, it’s just gorgeous outside. The summer has landed here. I think we just had the summer equinox. Every morning is beautiful, and you can mow your lawn till nine o’clock at night.

That’s awesome. I’m in San Diego. And it’s also nice, and the hummingbirds are flying around the feeders. But I talked to a friend of mine in Berlin this morning. It’s 104 degrees there.

Well, that is hot. It’ll get close to that at some point this summer.

So you just came back, I don’t know, it’s recently from Bonnaroo–where you are running the Hay Bale Studio. Can you tell people what Bonnaroo is? And I love what you did with the double-wide.

Oh, cool. Yeah. So this was actually my 15th year doing that. And the Bonnaroo festival is a festival of about 80,000 ticket concert goers. And then you probably have like another 20,000, and I’m sure on top of that are the staff, so you got 100,000 people who descend on Manchester, Tennessee. And at the beginning of this thing, at the birth of this thing, they basically just found a farm there that would let them start doing kind of a jam band festival. And then over the 15 to 17 years something that they’ve been running the festival, eventually, they just bought all this land. I don’t even know the exact number, and it’s so many acres of land down there that just belongs to this festival. And once a year, for about a week, it becomes like a city. I mean, it’s bigger than the town that it’s hosted in. But this year, I got a great statistic from somebody. And they said, “Well when you’re in front of the center stage, you’re looking at the big stage at a band. The furthest away campsite is two and a half miles.” That’s what somebody told me. So that’s how big this place is. And it’s just massive, massive campgrounds of people. And then there’s this area called Centeroo, which is where all the stages are. There is a huge stage, and the stages are kooky names, like “The What Stage” and “The Which Stage” and “That Tent” and “This Tent” and “The Other Tent.” And so it’s intentionally created like how I feel when I go into a mall. I’m just lost and festivals like that. It’s just music, and it’s just 100 plus bands playing over four days on all these stages just round the clock. If you don’t want to sleep you could just stay up, and it’s dance, DJs, and parties, and for a while, they had a 24/7 movie theater-going and a comedy tent, and there’s just food and people, and out in the campground areas, they’ll have many concerts and surprise shows. I think the band Paramore played a surprise unannounced concert out in one of the campgrounds. They’ll have these like pavilions out there. So it’s really an amazing place.

It’s so much fun. I’m going next year for sure. I was looking at all the campgrounds, and there’s some amazing food being barbecued and cooked. It’s camping like you don’t expect, I think.

It’s pretty cool, and I’ve seen your videos of you traveling to the Amazon to make films and sleeping in tents there. I bet you’d be very comfortable at Bonnaroo.

Absolutely but I think maybe I’ll drive across the country because I can put my camping equipment in the car, and then I can shoot on the way. Making a real adventure, I think I just might do that. I was looking at the way you set up the trailer that you have. You do in music, and I think the equivalent of what I do field production for films. You do a remote recording for your clients and one of which is the Bonnaroo. Tell us about this Hay Bale Studio. Love it.

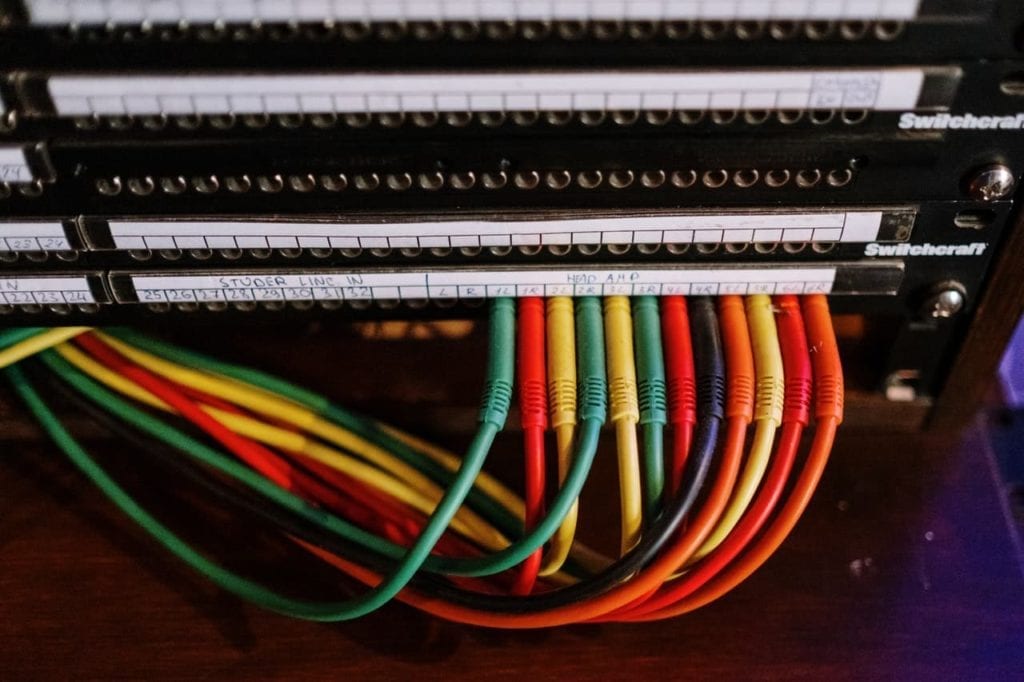

Yeah. So like I say, 15 years ago, I got invited to come down there. And this was by a guy who had put together kind of a radio station compound down there. So he had created this media area where radio stations could come from around the country and be present at the festival during the weekend. And then the bands would have a one-stop-shop to come do interviews, and hit all the media and do all their press all at once. And so he said, “Hey, here’s a budget, do you think you can come down and set up an actual recording studio on-site, and then just record all the artists that we can book to come in, and we’ll do interviews, and you record a few songs with him and everything?” And so in the same way that when a band travels to another city, let’s say band’s going to go play in San Diego, and they get there at five in the morning, they go to the radio station first. Play a few songs, talk about their upcoming show, and then go play the show. This is a chance for a band to do that in one stop right at Bonnaroo. And come in and record three songs with me, and then go do a series of interviews. And then they’ve sort of lined up all this press for their summer tour, for example. So we would set up a recording studio inside a double-wide trailer. And this year, we took down a 15-foot u-haul, just loaded up with drum sets and bass amps and guitar amps and acoustic and electric guitars and keyboards and then all the recording gear that you need to run a studio with headphones. And even a mastering engineer, and he brings down his rig. And it takes me and four other guys about a good eight-day stretch of just butt busting work, getting everything set up. Because I think as you do with your film shoots, you have to set everything up, and you have to lay it all out and see what you’ve got, make sure everything works. And then, very carefully, don’t mix it up with the stuff that’s staying back in your house or whatever. And pack it all up so that when you get on to this location, you’ve got everything you need. And so we’ll do that here at my studio first. We’ll spend a full day connecting and hooking up all the gear. And in the early days, a full day was barely enough time to even do that. And now the combination of knowing a whole lot more about what we need, and then just the technology has made things a little bit smaller and a little more portable. And we’ve sort of gone from analog to digital in 15 years. And now we can definitely get a full studio setup here. In a day, get everything all packed up, and then the next day, we pack up and drive down. Then the next day, we set it all back up there. And then, for four days, we’ll record up to 40 bands.

I didn’t know that you brought your own drum sets and everything. Because I was wondering how the bands would get in, set up, get out. Do some of them ask you, “Wait a minute, I want to use my own drums,” or they know you by now, right?

I’ll tell you what’s really tough is when a band comes in, and it turns out to be a lefty drummer. Because we’ve already got a drum set set-up with mics on it, we have to pull everything out, re-do like a horizontal flip of the whole drum kit, and then reconnect all the mics and do that. But we’ve done it, we’ve done it before, and we’ll do it again. You just have to be really flexible. I’ll tell you one of the rules that I tell all my assistants and my interns. One of the first things I teach him is don’t tape down that wire. As soon as you make something permanent, that’s when we’re going to have to change it.

We went through that at NAB, we set everything up, it took us all day, came in the next morning, and some things in the background had moved, and we had a terrible shot. So I wanted to just move one of the chairs over by a couple of feet, but it meant that everything had to be pulled apart and re-taped. Yeah, I understand what you mean. Also, I think it’s awesome you bring your own equipment, and you don’t rent a lot because you have to set it up ahead of time, right? You have to set up. But back to the Hay Bale Studio, so tell us about the sound insulation.

So it was the very first year and Sean O’Connell, who founded this thing. I went down there ahead of time to go have a conversation with him and sort of prep the site and take a look at it before I brought the studio down. Because Manchester is an hour away from Nashville, so it’s just far enough to need everything right there on-site with you, but it’s also close enough that if it was a true emergency, you could probably figure something out, Like have somebody else drive down. But anyway, I went down to go take a look at the site, and he’s looking around, he’s like, “It’s gonna be like this,” “the big stage is over there.” “They’re pretty huge sound systems. You’re gonna be soundproofed in there enough.” And we were like, “Jeez, I don’t know.” So then he thought, “I was just passing by. There was a farmer that was over there. And I wondered if we could just buy a whole bunch of bales of hay from him, and then just kind of stack them up around the outside of the studio, would that help?” And I was like, “That’s genius.” So we did that the first year and then from then on, for 15 years, we’ve always done that. And we’ve actually included more and more hay. We’ve actually gotten more advanced with our tech of how to stack hay around the studio and completely soundproof it. And now you walk in, and it looks like a huge stack of hay bales, this big, long brick of hay bales. And then there are stairs going up and two doors coming out the side. And you walk in the door and close it, and you’re in there, and it’s just quiet. I mean, you can hear a little bit. Cardi B was on the stage this year, that was maybe 400 feet from the studio, something like that. So once that gets kicking, it can get a little tricky, but usually, those big shows don’t start till the nights, and we’ll record during the day. But so for 15 years, it’s just been known as the Hay Bale Studio at Bonnaroo.

You’re gonna have to put hay bales underneath it to keep the vibrations away from Cardi B, right?

Yeah, well, the funny thing is, the trailer is up. So there’s a sort of a crawlspace under there. And early on, there was a year where a skunk was seen, and it went under. And it was like a hideout because it was like the skunks thinking like, what the hell is going on? There are 80,000 people in my forest, and so it’s trying to escape. So it escaped living under there. And then I think it finally went away. And luckily, it didn’t let us know it was there, and the skunk smell didn’t blast us. But so this the skunk has been our mascot for the studio. And so, every year, I print up t-shirts for the Hay Bale Studio, and they have just a pride Bonnaroo skunk on top.

Oh, that’s awesome.

It also turns out to be our band’s mascot from my band from 30 years ago. So it was a good tie in for me.

That’s awesome. It’s fate. It’s fate.

It is. You have to have a mascot, I think. Yeah, you do. I think I need one for OWC Radio, and we have to pick a mascot. I was listening to some of the recordings that you did with the Hay Bale Studio. Magnetic Zeros and just sort of going through the website and listening to sound is amazing. It’s really beautiful. So there we are, in this double-wide air-conditioned trailer with hay bales everywhere. I’m Italian, so every once in a while, I talk, and I hit the mic. I talk with my hands even when I’m in front of the mic. Can you talk to us about the workflow inside the space?

Sure. So the first thing we’ll do so we’ll have a band every hour, that’s sort of the goal. This year was the light schedule, and we had a light schedule of only 22 bands in the studio. But a band will show up at the top of the hour. I welcome at the door, “Hey, what do you guys got?” they come in, and they see what we’ve got. And we just immediately figure out what they’re going to need and where to position them. And I’ll tell you; it’s been a really interesting learning experience for me because it’s almost like the world conspires to make it way more complicated than it needs to be. So they’ll send us a stage plot beforehand, and it looks like the most complicated thing in the world, and they need 40-50 inputs from all these different things, and none of them look like they would even fit in the studio. And I’ve learned to just kind of take that, just kind of like, “Okay, I’ll just set it down. Looks good.” So really, that’s only four people, “Okay, we can handle four people.” And then they’ll show up, and then they come in, and they’ll say like, “Oh so and so’s,” “This drums, and bass, and guitar,” and then he’s gonna play banjo, fiddle and he’s acoustic, and they’re listing all this step-up, and then there’s like, “So and so is gonna sing,” and I’m like, “Alright, listen. So how many people are in the band?” “Okay, it’s only four people.” “Okay, great. So it sounds like 20, but it’s only four. And then you’re gonna need one mic, and you can just use that to play all those instruments.” “Oh, that’s much more simple.” And let’s see who’s gonna sing the vocals, and then you want to find out who’s gonna sing the lead vocals in the background because we have a different mic that we’ll use for the number one lead singer, and we have some different for the background singers. And then the other question is like, “Is the drummer really gonna sing on this or is he just gonna have a mic that’s sitting there the entire time that’s ruining my drum sound, and he just kind of goes like, ‘blub blub’?” And that’s all he ever actually sings on a song. So you kind of narrow that down pretty quickly. And then you’re like, “Oh, cool. So it’s really just two guitars, bass drums, and four vocal mics, and you’re singing the lead. Okay, cool.” And then we’ll have them positioned and set up in about 10 or 15 minutes. And they start warming up, and their instrument and they say, “I can’t hear myself,” and I’m like, “Well, hang tight. I’m still trying to get levels on everything. And once I have levels, then you’ll hear yourself in the headphones because that’s where the sounds are coming from.” And I like to mix it while the band is performing, which I think anybody who’s done audio-video, I’m sure other creative endeavors too, understands that the real time-killer in something is post-production. So the more that you can be prepared in advance, and the more that you can get done at that moment that you’re actually performing, the better results you can get, and the more productive you can be. Whereas if you save a whole bunch of stuff for later, then it sort of amplifies the amount of work by two by ten, or exponentially or whatever.

It does. But you can do that because you’re really good at this too. A lot of people couldn’t. I don’t think a lot of people could think on their feet the way you do. They want to wait, so they can think about it and listen to 20 tracks and mix it down and then have a go at it when nobody’s in the room. But I like the idea that you do it live because you’re capturing the performance. And that also means your music is in sync with them, right? So you get that rhythm going, and you’re one with the band. I love it.

That’s absolutely right. And I appreciate your comment. But truthfully, I can only do that now and do it well because I went through the initial steps of years ago of spending too much time trying it out and to sort it out later. And then I got a little bit better. And then you take risks, and you start stepping in and saying, “I’m gonna try doing something now, if I screw it up, maybe I can go back and fix it. But I’ll go for it now.” But I will have the band in there, and they’ll start performing, and I’m in a pair of headphones. So I will mix on a console, whether it’s a smaller digital one like we take now, or whether it’s a big 32-channel analog mixing console that took four people to carry into the studio. I’ll mix it while the band’s performing. So it really is a conversation. The band does something, and I ride the level according to what they’re doing. I’ll throw in effects and reverbs and delays. And tap the delay time and sync with the music while the band’s playing it. And all that stuff adds up so that we’re all performing this thing together. So you really have to have your head in the game, and you’ve got to be in performance mode. If the band is trying to perform well, and you’re just kind of phoning it in, that’s not a good combination.

No, it’s not gonna work.

Yeah, but that allows me to mix it while the band’s actually performing. And I’ve never heard the song before. I just say, “What’s the title of the first song?” “Okay, great. We’re ready for you.” And you just hope to god that like the vocals are loud enough for the first verse. And it goes to the back of the room. And our mastering guy records it, and then he’ll master it right away. And then it’s ready for radio and within the hour.

So talk to me about some of the groups that you had this year at Bonnaroo in Hay Bale.

Well, I’ll tell you one artist that came in that was really great to add to the list was Steve Earle. He’s a famous singer and songwriter here in Nashville, has been making records for many, many years. He’s even had an acting career. I saw him in a wonderful TV series called The Wire, years ago when I watched that. He was one of the characters. And then we had a number of other bands. Honestly, I probably have to go look at my band list. I’ve recorded so many hundreds of bands over the years that I forget the names, often less I’m actually looking at it.

You’re as bad as I am. People ask me what movies I’ve worked on, and I have to think for a minute. Or they’ll say, “Oh, you worked on this,” and I go, “Oh, you’re right. I forgot about that.” Well, I know that when I was researching you and going through the Hay Bale side, I listened to Magnetic Zeros, Father John Misty, Passion Pit, John Oates was in there, and the list goes on and on and on. You have worked with so many amazing people. It’s fun to think back on it. What headphones do you wear when you record them? And this sounds like a weird question, but it occurred to me that when you use headphones, are they changing the sound? What are some headphones that you would recommend to people that are recording in their studios?

Well, I’ll tell you, my recommendation to people is that you listen to some higher quality headphones, and you pick a pair that you like and works for you. And that you learn it. So once you’ve got something that’s good quality, and there are a number of good quality choices out there, the important thing is that you know it, and you understand it, and you get used to it, and then you get that feedback process with how you’re working. In fact, if you were to switch up the gear you worked on every single session, you’d probably never really get to know any of it well enough to really know what you’re doing. But I ended up years ago, finding a pair of Beyerdynamic DT 770s. And I love those. And so I’ve been using them in the studio. And then, when I started the Bonnaroo Studio, I used those. And that’s the only pair of headphones I’ve mixed on. I’ve had to buy a new pair in 15 years. But that’s the only brand of headphones I’ve used. And there might even be better headphones out there, honestly, because there’s a lot of choices. But again, it’s really important to just get used to something so that you have a sense of what to expect.

What are some of your favorite microphones for your podcast, for example? By the way, your podcast is awesome. I want to really recommend that to people. Tell us about your podcast and where they can go to listen in.

Sure. Yeah, so my podcast is called Recording Studio Rockstars. And it is interviews with recording professionals to bring the listeners into the studio talking about making records, talking about all the kind of how-to stuff, and what are some great techniques for recording different instruments. And then also sharing stories of challenges and failures and successes and advice for both people who are new to this and are looking for that inspiration and people who are lifelong veterans, who just are lifelong learners as well. So I’ve been doing that since 2015. So it’s been about four years now, going on five years, and over 200 interviews done now. It’s been a weekly show. I went through the beginning stages of how long should the show, but it shouldn’t be short. Should it be long? I edit it like crazy. And I went through all those stumbles until I finally arrived at a system of doing interviews with people where I go and prepared, and I let the interview be a live conversation. And at this point, I actually don’t do any editing anymore. I have a technique where I can drop edit markers and remove something if it’s a real clam or a mistake or something that’s gonna really screw up the show. I don’t want to make a guest look bad, for example, but other than that, in a two-hour interview, it’s mostly live. And so the podcast ended up getting longer, and it’s a weekly show. So we’re approaching a million downloads now for the show.

That’s awesome.

It’s going great. And I’ve found a lot of the tools that work well for me. This mic that I’m talking to you on right now is the same one that I’ve been using for the entire show for doing Skype interviews. If I’m doing a Skype interview, I use this. It’s called the MikTek ProCast SST, and that’s a Nashville microphone company. And what’s great about it is it’s just a USB that plugs into the computer. So Skype sees it no problem if I’m doing a Skype interview, and that’s how I do my audio interviews if they’re over the internet, and then it has a built-in boom stand that comes right up. So the mic is always in just the right spot for me and a heavy weighted base. And this is really important too. It has a mute button on it. So while I’m doing this live interview, I can mute my mic while the guest is talking. And then if I have to cough or make noises or scribble notes and they’re going to be too loud, there won’t be some noise that I have to edit out.

That’s awesome because I know if I’m shuffling papers or writing, or I want to type, I have to edit that out of my track afterwards. And that’s kind of annoying. So that’s a good point.

That post-production that will come back to bite you in the butt.

It will. Talk to me about this famous MCI console. Do you still use it? And I heard you talking about it in one of your interviews? Tell our listeners about it.

Okay, cool. Great. I’d love to. So I have a studio here in Nashville in East Nashville, Tennessee, called The Toy Box Studio. And it’s a home studio that I built, and it was my dream probably from about 1995, I think, to have a home studio. There was a time when indie rock was really happening; alternative music, the ability to start producing high-quality audio out of your home with a home studio was really becoming a thing. It really went with a culture of the kind of music that I loved working on. And so finally, in 2005, actually before 2005, I had started accumulating recording gear, because that’s what you do when you make records, or you make movies, or you do whatever, you pretty much take all your money. This is until you have a family maybe and you have kids, you take all your money, and you just basically spend it on new cameras, new microphones, whatever it is. So I was already collecting things. And then, in 2005, I started taking my garage and converting it into a really usable, wonderful recording space. So for the past decade, I’ve had this studio called The Toy Box Studio. And when I did that, I also was in the habit of scouring eBay and looking for cool gear to pick up from places. And I was working with another band out in LA, and we stumbled on this image of a vintage console that was made by MCI, which was Music Center Inc., And it was a company founded by Jeep Harned down in Florida. MCI was, I think, the biggest pro audio company in the 70s going into the 80s. That was US-based. So they were making large format mixing consoles, they were making multitrack analog tape machines, and some other stuff. And so this MCI board that was listed on eBay, we’re reading the history of it, and it’s the same one that came out of Criteria Studios, where it had a home all through the 1970s down in Fort Lauderdale, down near Miami, Florida. And it’s the same console that did Hotel California for the Eagles and the Bee Gees record Stayin’ Alive and Saturday Night Fever and Average White Band and the soundtrack to Grease. And it recorded Margaritaville, and it recorded Eric Clapton, 461 Ocean Boulevard, which had I Shot the Sheriff on it. Just like all these amazing records. And so I actually made an offer because it was sort of like an offer deal, and I didn’t get it. So then I got in touch with the sellers. It didn’t actually sell on eBay, but I got in contact with them. And I kept emailing them for a year and calling them. And they had decided that they were going to send it to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame; it was going to be inducted into the Hall of Fame and be on display. And I convinced them to sell it to me instead of putting it in and just collecting dust in a museum. I convinced them to sell it to me. Now, of course, it collects dust here while I use it. But I was able to build my studio and bring in this amazing piece of history. And it was a custom-built mixing console, and it had all this kind of cool new technology for the time. So there’s a whole routing matrix up at the time that our touch-sensitive buttons you just go up and touch it kind of like an electro touch-sensitive elevator button. That’s how I think of it. But it’s really incredible because it’s hand-constructed. When they made this, it was a kind of a prototype. And they sort of have these metal strips where they punched it out, and then there’s like a little seeing eye with the light behind it, a plexiglass thing that will light up when you touch it. But in the middle of each of those, you needed to have a piece of metal so it would make contact when you touch across your fingers, touching the metal strip and this little metal dot in the middle. And I saw one of them as the dots were coming up at one point. And I went over, and I was like, “Huh,” and I looked at and I grabbed it, and I pulled it out, and it’s a straight pin for sewing.

Are you serious?

Yeah. Jeep is so creative; he’s thinking of this way to build this complex new technology. And he’s not afraid to hammer out metal parts so that he could build this and just take a straight pin and just stick it right in there and make contact if that works. And so it’s like that. You open the top up like a car hood, it just opens up, and there’s just all these wires and stuff running everywhere. But the really tricky thing was when it arrived, it had no schematics to it. So a schematic, it’s the map, it’s the roadmap that tells you where things are going and how they’re connected, and how it’s all hooked up and how it works. So when something breaks, if you have a technician they’re gonna want to work on it, the first thing they do is say, well, show me the schematics. And then they’ll just trace down the lines and figure out what the missing thing is. So that made it really, really challenging to sort of modifying it or work on things that weren’t working because it was like buying an old model car from somebody. You have to fix it up, and you have to do work on it yourself. But I just progressed along and figured out how to fix some things. And I found a tech here who just wasn’t afraid of that stuff. He wasn’t afraid to get in there and just like figured out. And we got some of the things fixed that needed fixing. And then other things that don’t, we just work around them.

Well, you’re lucky you’re in Nashville. You have people like that all around you that understand audio. When you were talking, I was envisioning these scenes in the action movies where there’s a bomb about to go off, and you don’t know which wire to grab.

Exactly. The red wire or the green wire?

That’s crazy. Was there a moment where you said to yourself, “Oh, my goodness, why did I buy this thing?”

Oh, I’ve said that a number of times. But the answer is always the same, and it’s very clear. It sounds amazing. I’ve done what I think people do in the audio world, and I think they do in the filmmaking world, which is you integrate the old and the new. So I have this old piece of technology that has all this wonderful character and sounds amazing. But I don’t use it fully in the way it was intended. I use it to bring the sounds in through that, but then they go out. And I’ll patch them directly into my Pro Tools, which is recording the audio on the computer. And then you get that combination, so you get the sound quality, the microphones get to go through this great, cool sound in the mic preamps. But we still work on the computer and get the whole computer sound. And then there’s a whole section with faders where you can mix things. And if I want to say I want to put up a bunch of mics on a drum set, but mix it down through the console and then just record two channels into the computer, I can do that—that kind of thing. So you just figure out new ways to work that’s really great. And you try and take advantage of all the benefits of each old technology and new technology.

I know that you’re using a lot of OWC equipment. Where does that fit into your workflow?

Well, so the place that OWC has come in super handy for me has been in storage. So using OWC solid-state drives in the computer here, actually, my computer that I do all my pro recording on is still a 2009 Mac because that was one of the last iterations of the Mac Pro, which was like a real Swiss Army knife and a workhorse from Macintosh. Now actually, nobody calls it Macintosh anymore, do they?

We are dating ourselves. So are those the Envoys? What do you have in their SSD? You put the Envoys in there? Talk to me about getting all that work.

Yeah, I didn’t use the Envoys in there. I think I have the Mercury Pro 6Gs inside the Mac Pro 2009. They call it the “cheese grater Mac.” So what that did, it was really remarkable is it transformed this workstation into much more reliable. You don’t get the same kind of dropouts that you would get in Pro Tools recording audio in. One of the places I really noticed a huge speedup was in editing. So if I’m doing something called vocal comping where I might have 20 vocal tracks, and I’m trying to flip through them as fast as I can on the screen, while I’m working, and listen to one clip, listen to the next one clip, listen to the next one, and then decide which one I want to go back to listen to that one. And then I make a move, copy it into the cop track, and move on to the next line. That process could take you ages if it’s not going well. But if I have to go through a whole song and do that, it’s very intensive, but I can do it in an hour or something like that if I’m comping a vocal. Now, as soon as I put in the OWC, the SSD drives made it so that the computer could keep up with my pace. Hmm. And now, it just flips from one track to one another instantaneously. It’s really amazing.

It’s funny, I did the same thing to a laptop, a 2011 laptop, I replaced the hard drive with one of the OWC SSD drives, and it became a screamer. I was amazed. So what are you using for storage?

Well, I use those internally for the storage. While I’m working, I’ll just record those internal OWC SSD drives in my Mac, and then I’ll move it offline for archiving. And I have a pair of Mercury Elite Pros that are external that I can move things off to. I also have the ThunderBay 4, and that’s brand new, and so I’m actually going to be looking at ways to incorporate that into the studio system as well. That one is Thunderbolt.

I was gonna ask you, is it a Thunderbolt 2 or 3? I mean, you think about these tiny little things that run across the room, and they can make or break your workflow, right? I know I have a lot of Thunderbolt 3 that I’m using, but for example, the iMac that I’m using for this right now, it’s Thunderbolt 2. And then I have other things that are the old firewire. You’re probably using 800 firewire, right?

This one has 800 firewire, so I don’t think I can hook this computer up to a Thunderbolt system. I don’t think there’s a way to do that, and I’m still researching it. However, what I do is, of course, I have a Mac Mini that does have Thunderbolt 2 in it. And I also have a MacBook Pro 15-inch, which I think can do Thunderbolt as well. But what I’ve been using is the Mac Mini, and I hooked that up with a thunderbolt 2 to Thunderbolt 3 adapter, and voila, the ThunderBay works just fine off that. But you do have to carefully make sure that you have the right cables and that you have high-quality cables.

Yeah, Larry O’Connor, I did an interview with him about a week ago. And we were talking about what’s under the hood with USB-C. And a lot of companies are building these cables, and you don’t know what you’re getting. And all of a sudden, something will stop working, and what a lot of people don’t realize is check your cables first. Because sometimes it’s not the machine, it’s your cables. So how did you get started with all of this? I’m really curious when you were a little kid, what did you like to do? And tell me about young Lij Shaw.

Well, I grew up in a creative household for sure. My mom was a prolific oil painter. And when I was a kid till six years old, we were living in Brooklyn, outside New York. And so mom’s taken me into all these crazy, kooky artist galleries and probably saw a lot more naked people when I was a kid than most kids do.

Where in Brooklyn?

We were in Brooklyn Heights. So we actually had an apartment that looked right out over that Esplanade walkway, at one point. I’m sure it was a nice place to be at that point, but not like what it is now. Now, I don’t even know if you can afford to go up to the front door.

It’s interesting. We were in. I think it’s called the Red Hook area. I’m not sure about the Italian section. And I remember being upset because the family when my grandfather died, they sold the brownstone and I would have bought it. And have I bought it, and I probably would have been set for life. But yeah, so I understand. That was an amazing area very rich in terms of the culture and the food and the art galleries and the music. It must have been wonderful.

Yeah, it was really cool. I don’t know if you remember Atlantic Avenue is sort of the main thoroughfare in Brooklyn. But we had an apartment there, and literally, you just leave our ground floor apartment, walk up around the block. And then mom would show and run a gallery that was just on the other side of that block right on Atlantic Avenue. And so I could still find it today. It’s not a gallery anymore, but that was what growing up was for me. And so she always had us seeing music. And I remember both mom and dad sitting down at the piano to play songs now and then. And then, years later, when both my parents were divorced and remarried, my mom and my step dad also ran a movie theater. So we owned a movie theater, later on, up in Massachusetts when I was growing up. And it was one of these classic old art theaters. It was called the Nickelodeon, and then it became the Festival Fine Arts Theatre. And it had the big, beautiful red curtains that needed to be opened at the beginning of the movie, and the red velvet seats and everything like that. And it’s still a time capsule up there, too, today. But that was my first job, learning how to be a film projectionist.

That’s awesome.

So I was learning how to run carbon arc, film projectors, changeovers and stuff like that, and splice film together. Meanwhile, music at that point in my life was still just like, having fun taking lessons or like I was just starting to get my first guitar, and somebody introduced me to Jimi Hendrix. And I’m like, “This is cool.”

Yeah.

So it’s that combination of getting interested in music. Then going to school in college, I went to architecture school in St. Louis. So I wasn’t interested enough in music yet to decide that music is what I want to do. But I had been doing art, and I was good at math and good at some of the tech stuff. And then having that introduction to the mechanical side of things by being a projectionist and starting to want to learn how to fix my own car and things like that. All of that all through college. I did finish my architecture. I got an architecture degree, a bachelor of arts in architecture, a little bit reluctantly. I’m a good finisher, so I can finish something and make it to the end. But all through college, the most fun thing I did was join some bands and play music and bands. And that just blew me away. I never had realized anything as fun as being in a rock band and getting up on stage and playing a show and having a great time. And then hitting the road and going on tour and all that. And so it was after all that stuff, I finished college. My buddy invited me to go backpacking in Europe. We were taking the trains around for a couple of months. I was up in London, working in a pub, had gotten an apartment there, and was dating a girl for a couple of weeks. And then my brother calls me up, and he was in another story, this is just going all over the place.

This is exactly what I want to hear. This is fascinating.

So my brother called me while he was doing his junior year of college in Hong Kong. He was gone to, I think it was Hong Kong University. And he had just decided to pick the most far away obscure place he could think of. And he already sort of got interested in music and saw what I was doing. And so, at that point, he had decided I’m going to major in music while I’m in school. So he’s already studying piano and music. And he’s calling me in Hong Kong while I’m in London, and this is over payphones when it would take like 10 seconds to hear what the next person had to say some very awkward conversations. Then he’s like, “Dude, and I got a crazy request, man, I got a crazy idea. I’m in a blues band right now, playing drums in a blues band. And we’ve got regular gigs, and we need a guitar player. You want to come to Hong Kong and be our guitar player?” Then I get on. I’m like, “Dude, I’ll be there next week.” So I quit two jobs in London, and I left my apartment, and I left my girlfriend of two weeks. Who was great though, Angela, you were great. Sorry, it didn’t last.

Which was a long term relationship back then, right?

Yeah, exactly. Back then, it was a long term relationship. And I didn’t have any money. But I did have an Amex card. So I put a plane ticket on my American Express, and I flew out to Hong Kong. My brother picked me up at the airport, and I had absolutely no idea where I was going to stay or how I was going to survive, or where I would live, or how I would make money other than joining this band. But we did that. And I played guitar with him, and we started out having like five gigs a week, playing in this band. So it was actually pretty great. Then somebody invited me to just come live at their apartment with him—a professor who had a flat with extra rooms and was a fan of our band. And I was doing that. And the point of the story here is that we got an opportunity to go into a recording studio and record a song that the singer had written. It was kind of an anti-war song. And this is in 1991, so he’s writing about the Gulf War. And we went in, and I’m sitting there in the studio. And I was like, “Wow, there’s a lot of cool looking things in here. A lot of blinking lights,” and “What’s that thing with the faders that move up and down? What’s that thing called? And what’s that over there with the tape that rolls on giant reels from one side to the other?”

Oh, no. Was it an Ampex reel? Tell me it was an Ampex reel.

It might be an Ampex reel. I didn’t know anything about anything at that point, other than just playing some guitar and not all that well, either. And so I just thought to myself, I remember sitting in a recording studio in Hong Kong, I thought, “I want to do this. When I go back to the States after this trip, I’m going to find some way to learn how to record and make records.” And so I came back, and I show up at home and my dad’s welcoming me home, and he’s also wondering, like, “So what are you going to do now? You’re going to be living back upstairs again? You’re 23.” And I was like, “No, Dad, I’m gonna go find a school for recording music. And I’m going to learn how to make records.” I’d had some experience through college of like working on a four-track recorder and recording band rehearsals and things like that. So I already knew I was interested in it. But the idea of actually learning how to do it professionally was brand new to me. And I rode away to 50 different music schools because we didn’t have the internet back then. And then they just started sending me their fliers, and I found one that was in Tennessee called Middle Tennessee State University. They had just built a brand new $20-million facility. And it was sort of like the biggest, baddest facility for the lowest cheapest price. In fact, I even took it a step further. I moved to Nashville and lived here for a year, became an in-state residence, and then was able to get in-state tuition. And it literally cost me $700 a semester for full-time tuition to go to this brand new facility in college.

Oh, my goodness.

So I was right back into the bachelor’s program, and I went for another two and a half years and did that. And then that is how I learned how to start making records. I forgot what the beginning question was. I just took you out my whole journey.

That’s exactly what I wanted. I wanted to know who you are as a person and what your creative journey was. You mentioned that Ampex reel. When I first started out in radio many years ago, it was in a studio where we had the double reel to reel. We had to queue up our own sound and our own music. We didn’t have engineers the way they do now. So you have to do all your own work. You had the big Ampex reels next to you, and you’re talking to people, and you’re putting stuff up on the reel. It was great.

Oh, so was this doing radio production?

It’s radio at AFM Stuttgart Germany.

Cool.

Yeah, and it was fun back then, too, because we would leave each other recordings for the next shift. So somewhere, there are all these amazing recordings of us playing jokes on each other, and we have to talk offline about some of that stuff. It was fun.

I did that. My first internship was actually at a production house in St. Louis. And so I was just sitting there with a voiceover engineer, watching him work, and he was so fast. And he had a new digital system in there. There was the AMS audio file, and I think it was what it was called. Have you ever been to the dentist or something in the wheel in this thing, and they’ll go like put on a strange, goggle set and they’ll lean over to this weirdo computer? It was like that but for audio.

Yeah. So how did you handle the analog to digital shift? Was it hard for you? You know, this sounds terrible, but I still miss analog music.

Oh, totally. I mean, there’s a sound and a familiarity to a traditional way of recording on analog that we’re never gonna not miss.

Okay, so I’m not wrong with that, right? I’m not being a little crazy. Yeah, I missed the sound.

It’s very cool. And I mean digital is only now just really catching up with the sound quality of analog. And I don’t know if it’ll ever really all the way get there, but it’s pretty damn close now And especially consumer digital. Well, the very first thing you do is you just bump it all down to the cheapest, simplest format you can easily send to somebody over the internet, and you lose all kinds of sound quality. But for me, I actually embrace it. I find it to be a fascinating challenge. And I think one of the things to always remember is when you’re creating your own works is the moment you begin to make an excuse for the tools, just pause for a sec, and say, “What if I pull up somebody else’s movie right now on Netflix? Or what if I pull up somebody else’s record right now on Spotify? Does it sound pretty awesome? Okay, then I’ll stop making excuses about how the new technology is the reason why I’m having trouble.”

So you graduated. How did you first get started with your own studio?

Well, straight out of recording college, one of the first things I did was get an internship. So when I was in college, I moved down here to Nashville to learn how to make records. But I didn’t even know anything about the music industry. I mean, I learned pretty quickly that this was the hub for country music. But I didn’t come down here knowing that. So I wasn’t interested in that. I didn’t even realize that it was one of the three music cities. Like New York, Nashville, LA at the time. So that’s how clueless I was. So when I was doing recording, I thought like, well, I want to go back to where I had the most fun, which was St. Louis. I just want to go back there and go make records. But then I got an internship at a place called Woodlands Studios here in Nashville. And during my internship, I started seeing real record makers coming in. So for example, so I wasn’t in the studio, my internship was a technical one, and I was answering phones, but I was learning how to build the cabling and the wires and connect and build a studio, which is very, very valuable. And that actually helped me get my first gig right out of internship. But I did get to meet all the people who would come through because I’m in the lobby the whole time. And that’s where people like to slow down and have conversations. So right off the bat, Daniel Lanois came down to do Emmylou Harris’s Wrecking Ball album. And I got to meet him and have conversations with him. And he even came in. I was in one of the other studios on downtime. And as an intern, they would still give me a set of keys and let me bring in my own reel tape and put it up and experiment and learn how to use the gear. So I was in there listening to one of my own songs and working on it. And Daniel Lanois comes into the studio, and he gives it a listen, and he’s like, “It’s pretty cool. Hey, how you doin’?” And then he told me his guitar tuning, and he wrote it down for me on a piece of tape. And I remember I stuck it in the hardback cover of War and Peace. And so somewhere, I don’t know if I still have the book. I hope I do. But somewhere, I’ve got Daniel Lanois’ guitar tuning written down for me on a piece of console tape in a copy of War and Peace.

Oh, that’s awesome. I hope you find the book.

Yeah, thanks. Awesome. So I interned there for a while, and then they wanted me to hire me on, but the studio owner was like, “Here’s what I want you to do. I want you to come in at midnight, fix stuff till late in the morning so that it’s ready for the next session, and go home. And I was like, “I’m sorry. That’s not the job for me.” So I turned it down. My first job offer in a totally high-end pro studio. I actually turned it down because it just didn’t fit the vision of what I wanted to be doing. I wanted to be in the studio making records with people, doing the creative stuff, learning how to be a record producer. Of course, by turning down that job and starting my path to do that, the very next thing I did was deliver pizzas for six months.

Oh, you’re knocking down my theory. See, I have this theory that if we follow what we really love, and it did, it came true for you. It just wasn’t on the schedule you thought it was gonna be on.

Yeah, I mean, I didn’t even know what schedule it was gonna be on. If you want to follow your own path, it will take you where you want to go. It’s one of the things that I tell people, especially when I have new interns and students here. Whatever you decide to do, it’s probably going to work out. That’s what I’ve found. If you do it, it’s probably going to work out. So make sure you’re deciding what you want to do wisely with your eyes open carefully.

Absolutely. I believe that. And I always say a joyous life well-lived. That’s our legacy because that’s how you find what you’re meant to do. You have made so many musicians happy over the years with what you do. Are there some memorable moments you can tell our audience about?

Well, let’s see. Yes, there are. There are the versions of me being thrilled about a record that I have finished, where I just love the record. So, for example, there was a band called The Twigs, and we did Twigs too here, and we use the old analog tape machine. And we just got great sounds, and their song arrangements were wacky, and they were like, eight-minute-long songs, and there’s no way they’re gonna make it on the radio. But it was so much fun, and it was so creative. And we got to do things like break out the stylophone, which is a weird synthesizer, where it has two pens on it, and you touch the metal keys, and that plays the notes. And I think it was one of the sounds from Space Oddity. David Bowie’s record used a stylophone to get that. And we run it through distortion, and tape echoes, and the stuff that I just love to do, being super, super creative. But that band moved off to Oklahoma City. And I don’t know if they’re ever going to follow through with the band stuff. So there’s that kind of moment where you have the thrill of creating something that you really love, but the whole world might not know about it one day. And then there’s also the thrill of getting an award where something comes through. For example, my friend, Chad Brown, was mixing an album for Mike Farris, here through the MCI console, and then that album went on to win a Grammy. So now he was able to hang up a Grammy on the wall of the studio for being the owner of the studio. So you have those kinds of things. But I think early on, one of the big thrills for me too was when I finished playing music with my band, the singer was a writer, and he loves being on the road, I love being on the road too. And it didn’t look like the band was gonna really continue. So we weren’t going to get to go make music on the road that way. But he wanted to go and pick up stories from people all over, and I hit the road with him. And then we started this thing through the 90s that basically involved us hopping in a car, and I’d throw a portable recording studio into the backseat. And then we would just drive off to places like Wyoming and New York and Boston and North Carolina and the Smoky Mountains, and find people and find stories. And he would write about these people. I’d record their stories, their spoken word stories, which really I think is the birth of me wanting to get into podcasting at the beginning. And I’d archive their stories, and we’d record people’s music and record old-time fiddle songs in a depot in North Carolina. I recorded Memphis Blues legend Rosco Gordon in his apartment in Queens, New York, up in one of those top high rises with yelling neighbors next door and stuff like that. And I recorded the poet laureate of Connecticut in just a little office room. And it was a room in a publishing house in Willimantic, Connecticut, and it was a revolutionary publishing house. So just these really bizarre kinds of locations. And then we would bring all that stuff back, and it took me eight years to finish it, but I completed a full album for Rosco Gordon. And it turned out to be his final record. And then it got picked up by Dualtone Records here. And I had musicians, all these great musicians, the drummer from Wilco, and I had string players, I had Jeff Coffin who’s a saxophone player who tours with the Dave Matthews Band, and Béla Fleck and the Flecktones. I had all these musicians playing on this record that just started from an apartment room in Queens, New York. And then the poems we did with Leo Connellan, and we brought them back, and then we would record him reading a piece from this epic poem he wrote about hitchhiking across America. Basically a homeless drunk at that point in his life. And then, we would write a piece of music using the words from the poem in the music, and we intersperse that across 29 poems and fill up a whole CD with this. And then put that out ourselves. And there are not that many people in the world that have heard it, but it did get picked up by the BBC, and we got write-ups in other countries and stuff like that. It was filmmaking for the recording world.

So how do we hear this now? Where do we go to get this? Is it still available?

I think we’re in a transition stage, and we had a site called Poetry Scores. And that is the place to go find that stuff. I believe the Rosco Gordon record, and it’s called No Dark in America. And that’s online, you can find it on YouTube, you can find it on Spotify, and that’s still in print from Dualtone. And then some of the other recordings we just sort of released to friends and family and stuff like that. But we’re still in the process. So that evolved until later, we did more of that stuff. And then Chris started a nonprofit up in St. Louis called Poetry Scores and found some people up there because he was living up there, I was down here. And they took that next step further, and then they found filmmakers. And they started making silent films around all this music and poetry and then showing that, and that got picked up by some different film festivals. One of them was a poet named Ece Ayhan from Turkey. And so then, that film got a full write up and picked up in a film festival in Turkey later on. So just those kinds of connections, those are the things that really last with you through a lifetime, I think. The stuff that you start out with your closest friends, if you can hang on to that through your entire career, whether you become super famous, and then become not super famous, whatever, I feel like that’s the stuff that really sticks with you.

And that’s the stuff you’re meant to do. When I’m mentoring young people, I tell them to look around the room. And I tell them that it’s highly likely that the people that will end up being the most important to them in their lives are the people that they’re working with and playing with now. And they look at me like I’m a little crazy. But some of them come back years later, and they go, “You know what, you’re right.”

That’s great to hear because that’s the exact same thing I tell people. Like the young people, like, “Just look at all the stuff that’s around you right now. That is the key to your success.”

Yeah. Oh, my goodness. Lij, thank you so much for taking all this time with us. It’s really nice to meet the man behind the amazing music and the amazing poetry with music behind it. And I wish you all the best with Toy Box Studios. Where do people go to learn more about you? Where do you want them to go?

Well, you can go to ToyBoxStudio.com, and that’ll take you to my website about my studio here. If you want to check out my podcast, go to RecordingStudioRockstars.com. It’s also on iTunes. Very easy to find if you just search Recording Studio Rockstars. You’ll find it right there. And if you want to learn more about the Hay Bale, go to TheHayBaleStudio.com, and that is actually a page off my Toy Box Studio website. But that gives you a whole bunch of insight, and we got our links to our YouTube videos there. So you can check out some of these amazing bands we’ve worked with.

That’s awesome. One word of caution too, iTunes is going away. That makes me a little bit scared.

I’m not hip to the news.

Yeah, it’s going away, and I think they’re going to be moving people over to Apple Podcasts, and iTunes is telling us that all of our stuff is going to be safe. Yeah, we’ll have to bring you back on, and if the location of anything changes, we’ll make sure that we send people to your podcast. And everybody does need to listen to that because it’s pretty cool.

If your listeners, they’re probably already podcast-savvy if they’re listening to us right now. But for anybody who’s wondering how to get there, if you’re on your iPhone, you just swipe down on the screen type in “pod” for podcast. And then up pops the podcast app. Most people I tell this to if they haven’t done it already, they had no idea that a podcast app just lived on their iPhone waiting for them to use it. So that’s what you do, and then just use the search icon, and you can find any of these shows.

Yeah, and I understand that for people who are in business who also want to listen to that aren’t on the iOS version of what we do. There’s also a podcast app for Android, so you can subscribe to the rock stars podcast there. I think it’s wonderful. Thank you again, and best of luck to you. Break a leg with everything, and we’ll be checking back in with you again because you’re part of the OWC Radio family now too.

Oh, yeah, I love those guys. And it’s a pleasure to be here. OWC has been wonderful, and they’ve been a wonderful help with Recording Studio Rockstars and The Toy Box Studio, and the Hay Bale Studio. We just took all their drives down for that, and it was like primo.

And we wouldn’t be on OWC Radio without Larry O’Connor and all the troops in OWC. So thank you so much for sponsoring this. Thank you for giving me the opportunity to talk with amazing people like Lij Shaw. This is Cirina Catania, and I am signing off. And remember what I always tell you guys, get up off your chairs and go do something absolutely wonderful today.

Cheers! Thanks for having me.

Important Links

- Lij Shaw

- Lij Shaw – Facebook

- Lij Shaw – Twitter

- Recording Studio Rockstars

- Recording Studio Rockstars – Apple Podcasts

- Recording Studio Rockstars – Twitter

- Recording Studio Rockstars – Instagram

- Recording Studio Rockstars – Facebook

- Hay Bale Studio

- The Toy Box Studio

- 461 Ocean Boulevard

- AFM Stuttgart Germany

- American Express

- Ampex

- Average White Band

- BBC

- Bee Gees

- Béla Fleck and the Flecktones

- Beyerdynamic DT 770

- Bonnaroo

- Cardi B

- Chad Brown

- Chris King

- Criteria Studios

- Daniel Lanois

- Dave Matthews Band

- David Bowie

- Dualtone Records

- Eagles

- Ece Ayhan

- Emmylou Harris

- Envoys

- Eric Clapton

- Father John Misty

- Festival Fine Arts Theatre

- Grammy Award

- Grease (film)

- Hotel California

- I Shot the Sheriff

- iMac

- Jeep Harned

- Jeff Coffin

- Jimi Hendrix

- John Oates

- Larry O’Connor

- Leo Connellan

- Mac Pro 2009

- MacBook Pro 15-inch

- Macintosh

- Magnetic Zeros

- Margaritaville

- Mercury Elite Pro

- Mercury Pro 6G

- Mike Farris

- MikTek ProCast SST

- Music Center Inc

- NAB

- Nickelodeon

- No Dark in America

- OWC

- Paramore

- Passion Pit

- Poetry Scores

- Pro Tools

- Rock and Roll Hall of Fame

- Rosco Gordon

- Saturday Night Fever

- Sean O’Connell

- Space Oddity

- Stayin’ Alive

- Steve Earle

- Swiss Army

- The Twigs

- The Wire

- ThunderBay 4

- Thunderbolt

- War and Peace

- Wrecking Ball

Checklist

- Be adventurous with your love of music. Camp out at festivals and play, work, or listen to your favorite bands. Take tours and share your art with as many people as you can.

- Prep early. Make sure everything works before playing live music to avoid any sort of technical difficulties.

- Be as mobile as you can. Carry portable gadgets and equipment so you can travel light and without hassle.

- Go digital. Gone are the days of total analog equipment. Some musicians nowadays only need their laptops to play their music.

- Be flexible and resourceful. Oftentimes, musicians travel to unknown places where unforeseen situations may arise. When things go south or become challenging, if you’re properly equipped you can handle the situation smoothly.

- Use excellent, high-quality equipment that can withstand the active and hectic lifestyle of musicians.

- Invest in good quality headphones to ensure top-tier sound quality during recording sessions.

- Scout for bargain finds. Excellent music equipment doesn’t mean spending tons of money on them. Most of the time, there are great, even cheap finds on the Internet and local communities.

- Integrate the old and the new. Stick to some of the basics that work but don’t let yourself become outdated when it comes to music’s latest trends.

- Check out Lij Shaw’s website to learn more about his talent, services, podcast, clients, and more.