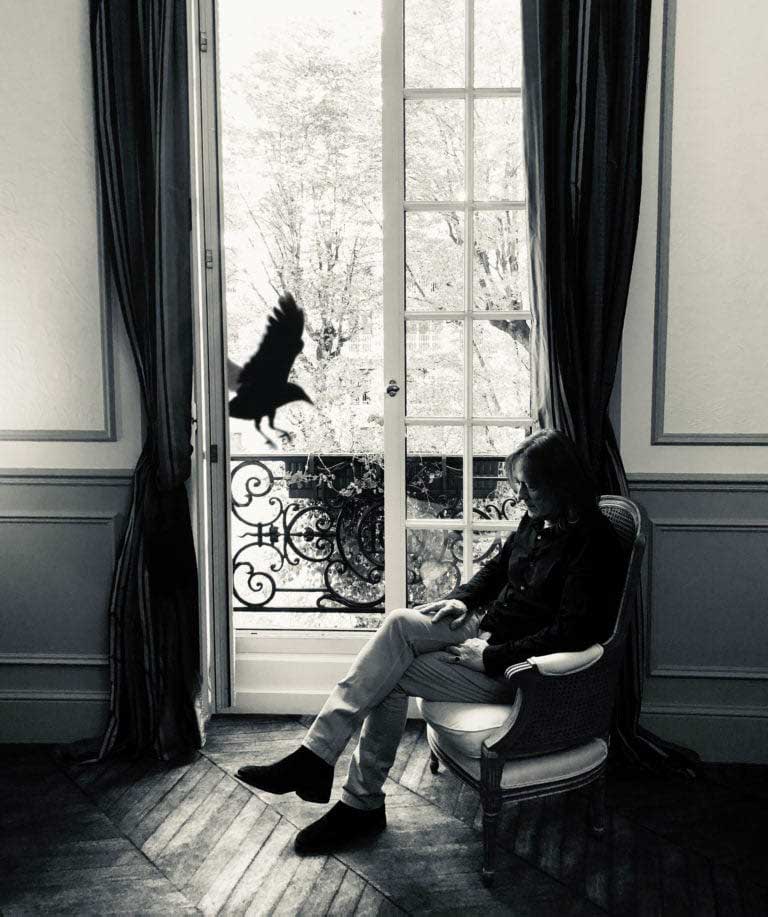

OWC RADiO Host, Cirina Catania, interviews Roger O’Donnell, an English composer and keyboardist best known for his work with The Cure, as well as bands such as The Psychedelic Furs, Thompson Twins, and Berlin. We talk about his latest album, 2 Ravens, his early days in East London, The Cure, and ballet.

He gained his reputation as a world-class keyboardist and Moog synthesizer expert, and O’Donnell’s body of work includes several styles and genres, some collaborative and some solo, with many written for the piano and others conceived for strings and chamber orchestras.

In April of 2020 he released his solo album, 2 Ravens, made in collaboration with vocalist Jennifer Pague that was inspired by the intense beauty and quiet melancholic solitude of the countryside where he was raised in rural England. He wrote it just after returning from a whirlwind non-stop tour with the Cure, landing him back home facing his own solitude.

Roger has said he was born next to the piano in his parents’ living room, and he first learned to play when his eldest brother taught him some 12-bar blues numbers.

He loves tech and enjoys using the most cutting edge innovations in the creation of his music, including equipment from OWC! Follow Roger at www.rogerodonnell.com

Note: Copyright (c) in any and all music in this interview remains with the creators.

In This Episode

- 00:18 Cirina introduces Roger O’Donnell, an English composer, and keyboardist best known for his work with The Cure, as well as the bands The Psychedelic Furs, Thompson Twins, and Berlin

- 04:43 – Roger shares a mishap from a company that pressed his record, 2 Ravens, and how he sorted it out.

- 10:05- Roger talks about how he met Jennifer Pague, an LA-based sound designer, composer, and songwriter.

- 15:19 – Why did Roger leave art school and switch to music?

- 21:52 – Cirina and Roger talk about musical instruments’ revolution in the years of the 60s to 80s.

- 27:37 – Roger tells the story of how he joined The Cure and the incredible albums they created while he was with the band.

- 33:48 – Roger talks about his album Love and Other Tragedies, where he played with cellists Julia Kent and Alisa Liubarskaya at the Grand Kremlin Palace in Moscow.

- 39:00 – Roger describes how OWC equipment works flawlessly and fit seamlessly into his workflow.

- 44:33 – Roger shares how he wants to buy a house in Maranello in Italy, where he a lot of his friends live.

- 45:49 – Check out Roger O’Donnell’s new album, 2 Ravens on Apple Music, Spotify, or buy the vinyl record on Amazon to listen to his music.

Transcript

This is Cirina Catania with OWC Radio. I’m speaking with Roger O’Donnell of The Cure, and I want to talk to him about his most recent work, 2 Ravens as well. There’s a huge story here, a long career, and I’m thanking OWC for sponsoring OWC Radio to allow me to speak with amazing musicians like Roger. Roger is a keyboard player, a composer, best known obviously, for his work with The Cure, but his solar orchestral work is amazing. And the 2 Ravens was performed with a string quartet and cellos. He also likes tech, and that’s appropriate because OWC radio is the marriage between technology and creativity. Although I think that Roger and I probably have something very much in common in that we’re a little bit old school. And we still love vinyl. Hi, Roger.

Hi. Yeah, I think we still love vinyl.

Oh my gosh, I love vinyl. I love vinyl. I had hundreds and hundreds of albums that I had collected over the years because I was raised in the military, and I could buy albums for $2.60 at the PX when I was growing up. But a lot of them were stolen. But I tell you, I went to buy 2 Ravens, and I’m ordering it on vinyl.

Oh, cool. It should sound good. We had some minor, well, I guess major technical issues on the first pressing plant we used the record company, I think we’re trying to cut corners and went to a cheaper plan. And as soon as I had the test pressings, I knew it wasn’t gonna work. And then I got a sample of packaging, and it was just not good quality. And the thing with vinyl now it’s not a standard product. It’s a premium product. And it really needs to be the best that it can. So I refused to sign those off. And we went to another plant in Germany, a very, very high-level plant that used to deal with more orchestral music because there’s necessarily a lot more space and air in that kind of music. I think you can get away with pressing a big black rock album, you got more leeway with vinyl, but if it’s a choir, it really needs to be good. It just needs to be special, and it turned out that way, so I’m happy with it now.

That’s awesome. I love vinyl because you can just hear everything. Digital recordings, as much as we all still love them, it’s just not the same for me. I love putting that album on. I love listening to every song on it in succession because I’m sure there’s a reason why you pick that order, right?

Yeah, and the spaces between tracks. I always spend hours with my mastering engineers, a very close friend of mine, Guy Davey, electric mastering in London. And we spent hours doing the gaps because it needs to feel like it either flows or you need a pause before one song and before the next song begins. And I think it’s really important of course you lose all that with digital. So many people just listen to single tracks these days, and as you mentioned, in the old days when you put on an album, and you went on a journey with the artist, and you heard the songs that they wanted you to follow the previous song. And I thought about that quite deeply about this record, about which songs should follow which, on what song should be on side A and which should be on side B. And we vinyl, generally you don’t get up and skip around because it’s such a pain.

You don’t want to scratch it either.

Yeah, exactly. So you genuinely got to capture the audience for at least one side, anyway, so

So what do you think happened with the first one?

I think it was just a poor quality plant. And I mean it’s a bit of a dark art growing a positive from the acetate from the cut. And I just don’t think they did a very diligent job. So I just sent it back. When you send something back, and they say, we can’t hear anything wrong with this, this our standard, then you know that you’re not even in a fight and a losing battle, you’re not even in the battle line. I don’t think they’ve surrendered. We’re not going to fight this. So then you either accept, or you have to take it somewhere else, which is what we did. And luckily, my label, they were okay with that.

What’s the label on the album?

Well, strangely enough, it’s kind of a bit of a full circle because back in 1979, when The Cure first released a record, they were released on Fiction Records. And that’s gone on through many different permutations. But the 2 Ravens was released on Fiction, it was on my own label, but through a licensing deal with Fiction Records and Caroline Distribution. And they’re great people. Jim Chancellor, who is the president of Fiction, Caroline, I’ve said this before, he’s just a music fan. He’s like from the old days of record company guys. He’s not corporate, in fact, he is terrible on the corporate side of things. But he’s just got so much enthusiasm for music. And also love the record and was prepared to go with it. And it’s not an easy record to market or put out there. But because this is a crossover kind of, it’s difficult to pigeonhole anything but this record, it being kind of orchestral but then with a kind of rock element with the vocals. It was a tricky one to market. But Jim believes.

It’s wonderful when you can find people that you can work with that can help you release something that’s so precious. It’s precious; this comes from a very deep place. And when you have a company that says, “Oh, it’s good enough,” that doesn’t work. Good for you for sticking up for yourself. Sometimes it’s not easy. It’s not easy to do, especially these days when the music business is changing so much, right?

Yeah, well, I’m in a lucky place that I come from. To make this music is my security and my place within The Cure. So, I can say no to people because it’s not everything to me because I have my work with the band to fall back to. And when I make a solo album, it’s purely out of love and passion for the music that I’m making. So if somebody says, oh, we’re not going to do this, I’m like, Okay, I’ll walk away and leave it until I find somebody that does. I’m not in a place where I have to secure a release. I’m only interested in working with people that share that passion. But of course, I’m lucky, and I’m very aware of that.

Yeah, you are lucky, but you’re also incredibly talented. So a lot of that goes into it. You could be lucky and not very good at what you do, and you wouldn’t get very far.

There are a few people like that.

Yeah, we’re not gonna name names. Talk to me about Jennifer Pague. She’s saying on the album, and the music video is just taunting.

I was introduced to Jen through my publisher, who also publishes her band Vita And The Woolf. And my publisher is actually a very old friend of mine, Daryl Bamonte. I have worked with The Cure for ten years. So he puts together, and I’ve completed the record as an instrumental record. And then he suggests, he said, “How’d you feel about putting female vocals on similar tracks?” and I was like, “Yeah, I’m open to it, and we’ll see if it works if it doesn’t, nothing gets lost.” So we sent her one track, and then she sent back about a minute and a half of vocals on that. And it was on An Old Train, that first one that we released. And it was just a revelation. It just really worked on many levels, and in ways that I hadn’t expected. My aesthetic is very European and British and rural, and then she comes along with this kind of American aesthetic for all kinds of American references, which we love. And it just worked. It was a really interesting contrast. If she’d been singing about flowers in the field, and birds and whatever, I think it would have been a bit twee, but this really worked. And it was a really interesting combination. I didn’t give her any pointers. I just let her do what she does. And I didn’t give her any lyrical ideas. And then she came over to London, and we recorded it in a week.

Nice. It’s a wonderful music video. Do you want to talk a little bit about the making of the music video?

That one in the train station?

Yeah.

My girlfriend lives in Berlin, and I was there for my birthday.

Happy birthday.

Yeah, thanks.

In October.

Well, it will be again this year. And I said, “Let’s go on the U-Bahn and see what we come up with. And that station, in particular, is very colorful. It is in old East Germany.

Which station was it? I spent a lot of time in Berlin. I’m usually there half of each year. But with this pandemic, I’m stuck in the house in San Diego. Do you remember which station it was?

I think it was Alexanderplatz.

Oh, there you go. Okay.

So we just went there with a camera, with an iPhone. Actually, we shoot it on our iPhone, one of those gimbal mounts. And we just wandered around and shot some video. It kind of came together. It took a lot of editing.

That is my next question. Did you work directly with the editor on it?

I did it.

You did the editing yourself?

Yes. We approached a video director, and he came up with some ideas. And I was like, It’s not really working. It doesn’t really make sense to me. And I was like, “Well, why don’t we just try?” It’s just pointing a camera, and editing is a bit more difficult. But I’ve done lots of stuff like that, and I enjoyed doing it.

What did you edit it on?

Oh, awesome. They came out with a new version yesterday. Did you hear that? There’s a brand new version of Final Cut. As of yesterday, 10.4.9 has a lot of amazing new features. And you’re gonna like this too because you’re probably working remotely with other people now. Working with proxies is a lot easier in the new version of Final Cut, so that’s gonna be kind of fun.

Oh, cool.

Yeah.

The problem with Final Cut Pro is I make my videos about once every five years, and it’s an intense period where I remember or relearn everything. And then, of course, the minute I stopped making videos, I forget everything. And then five years later, I’m like, Oh, I’ll have to go through all this again. And how do you do this and what’s that for?

Well, I have a theory about that. I think that because the creative process comes from such a deep and important place inside that, you’re focusing on that. And technology is a tool for musicians. But you studied art, and you actually attended art school. So why did you switch from art to music? What happened in your life?

Yeah, that’s kind of a story episode. I was studying graphic design, probably the finest graphic design school in London, at the time at London College of Printing, and it was fiendishly difficult to be accepted and get in. And I really loved it. But then I started playing in bands. And at the time, there was no blurring of lines. Now, I think one of my friends, Ian, who actually did the artwork for the cover, he went on to be a teacher at art school, as well as an illustrator. And he said they would actively encourage students to be in bands and being involved in theater and film, whatever. But when I was there, it was so rigid that there was no room for us to do anything else. And unless we were 100% committed to the course. I kind of dropped off, and I started playing in bands and missing tutorials because of rehearsals. And then the love of music kind of together. But they’ve always been equal, design and music have always been pretty much equal to me, and they run kind of strangely parallel. When I talk to my friend, Ian, we’re always kind of striving for the same things creatively. Me and my music and him with his art. So it stayed there with me. I just regret having left, I think, because, for the following three years, I didn’t do anything in music that made any difference. I could have finished my degree, but I didn’t.

I’ll bet, though, looking back on it. If you studied it for a moment, you would figure out that there were connections there, and there was a reason why all this happened in the sequence that it did. Isn’t that kind of the way it happens, right? It’s interesting. You have a daughter who’s an artist; she’s a graphic artist. So she must have inherited that part of your brain.

Yeah, she didn’t grow up with me. And she saw a drawing, and I said to her, “You know I went to art school, don’t you?” and she said, “No.” She didn’t know it until that. This is one of the very interesting things about having children about what they inherit, and what the things that come through in your DNA, and that was really interesting. She loves it. So she loves cats as I do. She inherited some good things from me. Luckily, she didn’t want to be a musician because that’s a bit of a killer. I don’t know what advice I would have given her.

It’s funny, I have children as well, and they grew up on movie sets. And neither one of them went into my business; one’s a doctor, one’s a lawyer. And I don’t know what I would have said to them had they said they want to make movies. I probably would have actually said go for it, but it’s different. So go back to when you were a little kid living in London, you were in London, right?

Yeah.

So your parents were musical too. Talk to me about what your household was like? What was life like for you as a little boy?

Well, I’ve got two older brothers and an older sister. And there was always a lot going on. My mom came from a big eastern family, and my dad’s two sisters lived next door. So there were a lot of people around. And the focal point of the house was probably the piano, which was in the dining room. And everybody, as they pass by, would sit down and play a song. My dad was in a youth orchestra when he was young, and my mom played completely by ear, but she could sit down and play any tune that you ask of her. And I probably from when I could walk and sit at the piano. And it gradually became a more and more important part of my life. Growing up in the 60s and 70s, when rock and pop music was really beginning, it gave you those kinds of opportunities or those kinds of horizons opened before you. Whereas in the 40s and 50s, not so much. But now it was accessible to be a pop musician or rock musician. And although I remember being at a scout camp, and one of the boys in the scout said to me, “I want to be a pop star,” and I looked at him as if he was from another. Just couldn’t conceive of what that meant, or why anybody would want to do it, and how you would do it. But then it goes, I started hanging around with bands, like in my teenage years and going to see bands and then becoming friends with them and realizing, oh, yeah, I can play the piano, I can join in. And the biggest problem was the pianos were not that easy to carry around.

You can’t carry the piano with you.

So I eventually decided that I needed an electric piano. And at the time, there were only about three choices. And I said to my dad that I wanted to do this. And he said, “Okay, well, if you get a job and half the money, I’ll give you the other half.” So he encouraged me from the beginning, even though I don’t think he ever realized what would happen. So I used to set it up at home. And it was all very encouraging, but I think nobody really understood what it meant. It was like, beyond the realms of that world, I think.

I think life in the 60s, 70s and 80s was unbelievable. It’s hard to describe it for people who weren’t there. It was the heyday of music.

Yeah. And horizons and things were getting bigger, faster, more colorful, you could do amazing things, and it seemed like it was limitless. Growing up in East London in the 70s, it wasn’t exactly Hollywood. It was tough, and we didn’t have a lot of money. But even so, you didn’t worry about that. There were things like Concorde being invented and flown, and musical instruments, especially for a keyboard bag. Going back to technology, it was an incredible time. It was like instruments were being invented. It seemed like every week, and there was something coming out. And I really love technology, and my go-to answer will always be the piano. But what you can do. I have a very close relationship with the guys at Moog. And just talking to the engineers, I’m very good friends with Cyril, who is the engineer and chief designer. And it’s just amazing to have that relationship with those guys and be able to talk to them. Half the stuff I can’t understand. He says to me, what do I want in a synthesizer, and I say, “I want any.” And he says, “What about if I gave you this?” And I was like, “What? You can do that?” And then it just blows you away. So yeah, that year of recording a MIDI and computers, the thought that you could play into a computer, and then it will play it back out to you. It was just incredible. So it was an era of I’m not sure we’ll ever be seen again.

Yeah, I’m a little sad about that, actually. Honestly, I want more of it. I don’t want it to be gone. There’s an aspect of those kinds of memories that tend to be a little bit melancholic.

Exactly. Talking about Concorde, and when that last flight landed, I cried. It was like that really underlying the end of that kind of technological development. And now we’re faced with all kinds of constraints, environmental, and things that do with health and money, and I don’t know where we go from here, but let’s not get too depressed.

No, actually, I don’t often look back, but when I do, it is a little bit melancholy that comes in. But then I start to say I’m so lucky. I have an ashtray in the living room that I’ve kept all these years. Remember they used to give you these porcelain presents? When you were on the Concorde, you’d get these little presents. You go to New York, and you’d fly–I forget, what was it? Two and a half hours or something? Crazy like that to get to Paris.

Three and a half.

It was three and a half, and it was so quiet. The plane was just like gliding above the clouds. And yeah, those are wonderful memories. But I do believe that there are other things on the horizon for us. And you’ve talked about you’ve done some of your great work and that you don’t listen to happy music. Why is that? I want to know, you have to tell me, why do you not? You don’t dance in the kitchen?

No, I can’t be seen to be dancing. There’s a famous quote from somebody who only ever said one famous thing, and I can never remember his name, but he was a French philosopher. And he said, “Happiness writes white on the page.”

Oh, wow.

Yeah, it’s great. You can use that whenever you want. There’s a great richness in sadness and despair that I don’t think there is in happiness. I can’t write happy music. I just, I’m like, okay, whatever. Yeah, I’ll listen to it. But the emotion that comes from great, dramatic works. And when you think about what the composer was going through, and you can feel it. And for me, the greatest achievement is for somebody to say to me, explain to me what I was doing in a piece of music. Explain what my mood and sentiments were. And if I can convey that simply in music, then that’s an amazing achievement.

It is. You did last year, what? Over 50 shows with The Cure?

Yeah.

How on earth?

We got love happy song.

Yeah, so talk to me about your years with The Cure. You’ve been in and out of it.

Yeah. Okay. Well, when I joined The Cure in 1987, it was a part of, like the, I guess the final step in a development that had gone on in my career. And I was playing in Psychedelic Furs, and then I got asked to join The Cure. I finished American tour with the Furs and flew to Dublin, and started rehearsing with The Cure. Two weeks later, I was back on stage in Vancouver or somewhere with The Cure. It was a crazy period, talking back about the 80s that you can go in from one massive band to another. And it was an amazing time back then because The Cure was really on that upward. From The Head on the Door had been released, like two years previously, and they just finished Kiss Me, Kiss Me, Kiss Me, which is the album I joined to perform. I got a pre-release cassette of Kiss Me, Kiss Me, Kiss Me, and I put it in my cassette player. And I knew within three seconds that I had been playing that band because it was so fantastic that I’d never heard the like of before. And then from there, we went on to write and record Disintegration, which was like a huge record, I think not just for us, but for the music in general. And that was an amazing time. I look back at that period, I think, yeah, I was making this incredible album. We thought it was good, but I had no idea. I was chatting with Robert recently, and I said, “We were just making the record. We had no idea it’s gonna be that fantastic.” Because he said,” I always knew it was good.” I had no idea. I just thought we were just making the next year’s record, but it turned out to be a career defining record. And then I was kind of overcome after that record, and it was like, I’d spent my entire career trying to achieve that kind of success not just monetarily, but creatively as well. And then I was just kind of lost, and that’s primarily why I left the band then because I just didn’t know where else to go. I was just like, okay, I’m here, where do I go from here?

So I left for, what was that? Five years at that time? And then when I came back, I was ready to come back. It was like Robert wanted me to come on play on the next record, and I flew to England, and I said, “I’m back, I’m not leaving.” And we were recording that record in that period, and it was ten years. And then I guess, after that ten year period, I needed to find myself again, in a different way, but this time creatively. I needed to express myself as a solo artist. And having learned everything that I had built up over the years, I started a record label and a publishing company. And I wanted to get into that side of things, and then finally when I came back in 2011, it just sort of felt natural. And we talked to each other, and we said, “Look, if we can’t get on there at our age, we never will, and we’d known each other half our lives.” We’re like a family, and it’s very comfortable, and we knew each other so well, and the performances last year were absolutely amazing. Last year started off kind of weird with the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, which is, English musicians are pretty self-deprecating and not prone to slap each other on the back and say, “Wow, that was great!” There’s not a lot of whooping goes on backstage after we play. So to be awarded some kind of, it was just very weird for us. But that was interesting, the way it affected us. And then we played at Glastonbury in the summer, which is a big, big thing for British bands. It’s our biggest festival, to be honest. It’s like a national institution. And we played so well at that show. And it was on BBC TV, which is our station. I’ve looked across the stage and see these guys that I played with for 30 years, and it just all felt right, and it continues too.

Well, that’s nice. It’s kind of like being in love, isn’t it? When it works, it’s really, really good, and when it doesn’t work, it’s pretty awful.

It’s more like being married than being in love, not you need to be mutually exclusive.

So do you have plans to move to Berlin? I love Berlin.

No, it’s not one of my favorite cities.

Oh, it’s not. Why?

I find it so kind of punk; I’m past that. I was in that forty years ago. But it’s fun. I like going and Mimi, my girlfriend, loves it.

Yeah, I think the thing I like about Berlin is I think you can find a corner of Berlin to fit whoever you are, and people don’t judge. That’s the one thing I do like about it. Well, you survived last year. But talk to me about, there’s this wonderful work, Love and Other Tragedies. Talk to me about Tristan, Isolde, on this big stage with cellos. It’s beautiful.

Oh, the ballet? So I released an album in 2015, Love and Other Tragedies, which is based on his three movements in each suite, which is three classic love stories. And I did that with a friend of mine, a cellist, Julia Kent who’s absolutely an incredible cellist.

Yeah, she’s wonderful.

And then I’ve been toying with the ballet world for about eight years now. And we’ve written an entire one-act ballet based on the story of The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde. So that’s kind of in the background. And then and I ended up spending quite a lot of time in Moscow, and I have an incredible mentor there called Andris Leipa, who is the son of Māris Liepa, who was a hugely famous Soviet era ballet star. Andris has really helped me navigate through that world and taught me so much. We sit for hours and drink tea and just talk about anything. And I asked him the most naive questions about ballet, and he never bats an eyelid and just tells me everything. And then I’ll stand on the side of the stage with him. And he will talk me through everything that’s going on on stage and explain what’s going on between the dancers. And so an opportunity arose for me to do one thing at a gala that he was putting on at the Kremlin Palace in Moscow. And so we used one of the pieces of music, from Love and Other Tragedies’ Tristan and Isolde and we performed it with piano and four cellos, and they were students from the Moscow Conservatory. And we performed it with two of the cellists from the Bolshoi. And one of the most amazing parts of that little story was that we rehearsed in the Bolshoi in the famous rehearsal rooms. And that was like a dream come true.

I worked with choreographer Nikita Dimitrioski, who is really talented. But the most interesting thing was, we’d be performing the music live, and in my world, I have room for interpretation. So, things generally come out a little different every time I play them. The ballerina, Masha Maniachenko, was a little fazed by this, but in the end, she really loved it. Because they never get to work on stage so closely with live music. And so we did a run through the piece, and then we stopped. And then I was playing apart with one of the cellists just to show her something. And now she just got him started dancing. And it was like one of those incredibly special moments that I’ll never forget, in one of the famous rehearsal studios at the Bolshoi. So that was a night to remember. And then we played at the Kremlin Palace to 5000 people. And luckily, the piano was facing away from the audience, so I wasn’t quite as nervous as I can get in most situations. And I was more concerned with keeping the four cellists on track. And of course, there’s this single, long, sustained note at the beginning on one of the cellos. And the music fell off a music stand, and she stopped to pick it up. But luckily, I was able to edit it in Logic.

Oh, my goodness.

I cleaned that out. But yeah, that was an amazing experience. See, there’s the beauty of having that kind of tech, backed up to pretty much orchestral classical kind of world so that I was able to do that. And I dropped in a sample of another cello to cover that dropout.

That’s the beauty of being able to work in both analog and digital together. So you use Logic, and you have some OWC equipment too, right?

Yeah, I’ve got some hard drives, which are amazing that I got in Austin last year when we’re playing on tour there, and a little interface, which should be really nice. The most important thing we’ve taken from it is that it does its job, I don’t have to read a manual, and it does it seamlessly, quickly, and flawlessly. You cannot have any doubt about a hard drive because of your life’s on it. As many backups as you do, there’s always one last tape but doesn’t get backed up. And you need to depend on that equipment, and these have been faultless. I’d recommend them to anyone. They’re nicely designed, and they’re really nice people at OWC. I met the President.

Larry?

Yeah, Larry.

Larry O’Connor really cares about what he does. He is a world-class engineer; the man has a brilliant mind. But he’s like many people who are incredibly gifted. He doesn’t flaunt it. It’s like you were surprising when you got into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame and didn’t quite know what to do about that. I think Larry must look around and everything he’s accomplished, hundreds of millions of people around the world using his equipment. And you wouldn’t know it by speaking with him. But that’s good, that’s really good. I’m glad that they’re keeping you happy because that’s how I met them. I’ve been using their equipment for years, many, many years. There’s a piece called the Underworld that looks really difficult. But it’s worth it, right? Tell me it’s worth it.

Oh, boy. We when we played that live. So Alisa, the cellist, played it with me. It just goes across all time and bars. So when we played it live, we were just staring at each other just to try and keep it right. And that was hard to play, really hard. And when we did that album, we played at a famous church in East London, St. Leonards in Shoreditch, and I did too much that day. I produced the show and in charge of everything, and then after the band turned off, and that’s always intimidating. And I didn’t enjoy it, and it was too stressful. If I ever do that again, I’ll have a producer to put everything together.

You need a producer.

But that song nearly killed me, and Alyssa playing it on a cello is pretty heavy duty.

I love that you said you don’t even know what time signature it’s on.

It just kind of goes across everything. That’s one of the confining things in music is when you sit down, and you play freely, and it goes across all time signatures, and then you kind of have to drag it back in some to make it understandable to other musicians and to the listener. And it’s kind of like a writer when you’ve got this massive creativity in your head, and you then have to funnel it down into something that’s understandable. I find that quite a struggle because I like the freedom of when it’s in your head, but then there’s that rush to get it down onto the computer screen. And a lot is lost there but of course, what’s gained is that other people can hear it and understand it and play it. So it’s roughly in 4/4 anyway.

Roughly, but I listen to it, and I thought, I wonder if this is a metaphor for your life in some ways.

Or the Underworld.

Well. No, not the name but the music itself and the fact that you don’t know what time signature it ends.

Yeah, it could be. I like the Italian translation of the Underworld is Il Regno Dei Morti, which is the kingdom of the dead. I love that title.

That’s nice. It reminds me of the Dia de Los Muertos. There’s a lot going on in that world.

Yeah. Let’s hope so because we’re gonna end up there.

We are. Are you in isolation there?

No. Well, I’m in the middle of nowhere in the countryside. So life really hasn’t changed apart from the fact that we can’t travel anywhere. We’re thinking of going to Italy on September 2. I’d like to buy a house there. I’ve lots of friends around Modena and Maranello, but now it looks like they’re going back into lockdown. And it’s just such a struggle. For the most part, life hasn’t really changed here. We went to London recently, and boy has life changed there. It is deserted. It’s apocalyptic. So I don’t know when things are going to change. I’m lucky I’ve got things that I do. I fly, and I like cars, and I have lots of toys here. So I’ve got things to do, but it can’t go on forever. We need to get back playing again.

Absolutely. What’s your favorite car? I have to ask. I love cars, too.

Oh, I’m a big Ferrari fan.

Oh, there you go. Nice. And where do we go to get your new album? Tell people.

Well, you can listen to it on all the major platforms, Spotify, I’d recommend Apple Music. All of those streaming services. And if you want to buy the vinyl, I think that Amazon has got 90 signed copies, and those are the last 90 that I think are available. So if you want to find a copy, there you go.

There you go. Go on Amazon and search for 2 Ravens from Roger O’Donnell. Get your vinyl copy. You want to listen to this on vinyl. You’re not done yet. You’ve got a lot of years to go, but what do you think is the one thing you have learned that is going to propel you into your future? If there’s one memory that you tell the family that will live after you, what would it be?

There’s another saying, and I don’t know where it came from that I try and carry with me, which is “Don’t spend all your life making somebody else’s dreams come true, and make your own dreams come true.”

And you’ve done that.

I leave you with that.

That’s wonderful.

Well, there’s a few things. I’d really like to put this ballet together with Dorian Gray. That’s such a huge endeavor. And I like to do things that I can control myself, and that’s way out of my control frame because there’s so many people involved and so much money. I’d like to think that that could happen. That we’ll see.

Well, maybe you just get a producer to work with you that you can trust.

I really need to work with a ballet company. It is too difficult to do as an independent. The music is finished, and the libretto is done. And I know who I’d like to dance Dorian. And in fact, he said he would.

And you can’t talk about that yet. I’m gonna have to check back with you in about a year and see where you are with everything. Roger, thank you so much for taking the time to do this. It’s been wonderful and for being so frank about who you are and sharing your life with us. I think you are not just because of The Cure, but because of who you are with everything you’ve done and inspiration to a lot of people. And so I do wish that you continue to go on living your own dream. And thank you so much. That was Roger O’Donnell. He is an amazing keyboard player, composer, performer, and everyone you know what I always tell you get up off your chairs and go do something absolutely wonderful today, even if it’s in your own home. This is Cirina Catania with OWC Radio. I’m signing off, and I’m saying goodbye to Roger until the next time. Thank you.

Important Links

- Roger O’Donnell

- Roger O’Donnell – YouTube

- Roger O’Donnell – Twitter

- Roger O’Donnell – Facebook

- Roger O’Donnell – Instagram

- 2 Ravens

- 2 Ravens – Spotify

- 2 Ravens – Apple Music

- 2 Ravens – Amazon

- Love and Other Tragedies

- An Old Train

- The Head on the Door

- Tristan and Isolde

- Il Regno Dei Morti

- The Cure

- The Psychedelic Furs

- Alisa Liubarskaya

- Andris Leipa

- Cyril Lance

- Daryl Bamonte

- Jennifer Pague

- Jim Chancellor

- Julia Kent

- Larry O’Connor

- Māris Liepa

- Oscar Wilde

- Bolshoi Theatre

- Caroline Distribution

- Fiction Records

- Glastonbury Festival

- Kiss Me, Kiss Me, Kiss Me

- Moog Music

- Rock & Roll Hall of Fame

- The Picture of Dorian Gray

- Concorde

- Final Cut Pro

- Logic Pro

- OWC

Checklist

- Explore the world of music and let it help you discover more about yourself. Honing one’s skills in music has many benefits for a person’s cognitive skills.

- In the music industry, make sure you’re working with the right people. Having a team you can trust plays a huge role in your career’s progress.

- Materialize your vision. Write it on paper, create the notes, get up and record a song in the studio. Without implementation, ideas are just dreams.

- Keep creating music. Be consistent with your passion and understand that success is more hard work than vision.

- Collaborate with other artists. Sometimes trying out something different can be good for you.

- Start early but know that it’s never too late to chase after your dreams. The best time to start is now.

- Express yourself through music. It’s an excellent medium to share your thoughts and feelings so your message can reach more people.

- Find a mentor who can guide you through the crazy world of the music industry. Having someone who can teach you and keep you grounded is a gift.

- Trust the process. The journey is going to be a long and winding road but everything is worth it.

- Check out Roger O’Donnell’s latest album, 2 Ravens on Spotify, Apple Music, and Amazon.