OWC Host, Cirina Catania, talks with world-famous composer and producer, British born, Simon Franglen, who started out as a musician and record producer, and soon began working with composers such as John Barry on the soundtrack to “Dances with Wolves,” David Fincher’s “Se7en,” and David Cronenberg’s ”Crash.” He produced the vocals for “Moulin Rouge” and programmed on the “Bodyguard” soundtrack. And his collaborations with artists over the years include the likes of Whitney Houston, Michael Jackson, Quincy Jones, Celine Dion, Luciano Pavarotti, Toni Braxton, and Madonna.

James Cameron’s “Titanic,” sailed him to a Grammy Award for Record of the Year as producer of “My Heart Will Go On,” and Golden Globe, Grammy Award, and World Soundtrack Award nominations for the theme song from that same film, “My Heart Will Go On.”

He worked alongside James Horner for many years as arranger and score producer. When Horner tragically died in 2016, it was Franglen who completed his score to “The Magnificent Seven”

All in all…he has over 400 major credits in genres ranging from English Grime rap, to classical and everything in between.

And his latest works are equally stunning, with ground-breaking 3D audio mixes for installations in the U.S., Europe, and China.

Cirina caught up with him during a recent trip to his studio in Hollywood and they geeked out about his gear and his workflow, including his love for all the OWC equipment that has stood loyally by him for many years! It was an enlightening conversation!

For those of you who are interested in creating music, Simon shared his process we are happy to pass it on to you! Stand by this is going to be fun!

In This Episode

- 00:01 – Cirina introduces Simon Franglen, a composer and producer of film and classical music.

- 04:28 – Simon talks about the various monitors he uses in his studio in Los Angeles.

- 08:46 – Simon explains the advantages of using Pro Tools in composing and why he prefers using it over other platforms.

- 12:59 – Simon shares how he has tons of analog equipment but prefers the flexibility of working digitally.

- 17:31 – What did Simon like to do when he was five years old? At what age did he fist become interested in being a record producer?

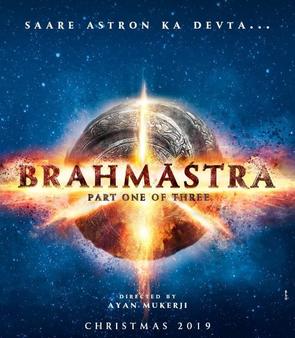

- 20:01 – Simon talks about the Bollywood film, Brahmāstra.

- 24:11 – Simon discusses the interesting experience he had working with international composers in making The Birth of Skies and Earth.

- 30:24 – Simon describes the workflow of producing projects with their convenient setup of working remotely.

- 34:03 – What is some of Simon’s favorite OWC equipment and how does it make his workflow more efficient and seamless?

- 41:44 – Follow Simon Franglen on his social media accounts, and visit his website, www.simonfranglen.com to learn more about his amazing works.

Transcript

Simon Franglen is in town. He’s in Los Angeles not much longer, however, and I think we wrangled him because I heard from a little bird that you use OWC equipment. Of course, since this is OWC Radio, I would be remiss in not speaking with you, right? Hi, Simon.

Hi, how are you?

I’m good. I’m very good. Simon, you’re in Hollywood. Can you do me a favor? Can you kind of look around the studio you’re in and tell our audience what kind of gear you’re using and a little bit about your process. I know you have a current project you can’t talk about. You can’t talk about the one you’re working on now. But perhaps we can use the example of the 2019 release of The Birth of Skies and Earth because that was a huge project, and perhaps we can talk about how you managed that one?

Well, if I look around from where I am, I’m looking at a 55-inch OLED main monitor, which I moved to use touchscreens, and I’d like backlighting, so they don’t sort of blast your eyes out, especially late at night. And then that’s feeding into a 28-core Mac Pro 2019 with 384GB of RAM and 32TB of OWC RAID internally.

Oh, that’s awesome. So you’re using the OWC SSDs inside the Mac Pro?

Yeah. The NVMe writes,

Aha, you know, they just came out with a new case for those. You can actually carry some of those projects with you and use them on your laptop. If you’re thinking about work, you can actually hook the Envoy Pro to the back of your laptop with the NVMe in it. It’s wonderful.

I have external 4M2. I have the 4M2s externals as well as the 4M2s internals. I have two boxes with 8TB in each, which I used to carry stuff around as well.

So you have a studio in London, and you’re currently in a studio in LA. Is that your second place, or are you just traveling?

Yes, it is.

Okay, you have a full setup. You’re looking at your 55-inch OLED. What manufacturer do you use for your monitor?

I’ve used the Sony, but it’s the same panel as the LG. It’s basically the same thing, but I like the Sony. It was the one that came out that had the sort of angled stand on it and made it look a bit like an artist’s easel, and it works perfectly. I have it set up on my keyboard workstation. I have a Yamaha 88-Note Keyboard in front of it. And then a load of little side panels used to control different things like iPads and androids of various sorts that go with different remote controls. Then to my right is an iMac Pro, which is a, I want to say a 12-core. And that’s got 128GB in RAM in there. And then I’ve got two Mac Pro 2013, they both have 128GB in as well.

Okay, I have to ask, I don’t have the equipment you have, but I’m looking at four different computers in front of me. What are all those different computers doing for you on a daily basis? What do you use them for?

So I have them running samples. So I write in Pro Tools, which is unusual. Most composers tend to write in Logic or Cubase. And I have to say, I really, really like Logic, and especially with the way that it integrates with the new Mac Pro, it is amazing. And then, what I use is a thing called Vienna Ensemble Pro, which is a piece of software that allows me to network together and feed sound from them. So I have one computer, for instance, that has all of my string libraries. And then I have another computer that has my brass and woodwinds, and another computer has all my percussion in it and another, and so on. So that I’m using different libraries so that the central computer, the Mac Pro 2019, is acting sort of like an input machine. And everything else is being served off the different machines. I can do it all internally in the Mac Pro. I find that serving it off different machines just seems to work better for them. The new Mac Pro is ridiculous. And when I have driven it with hardware, I’ve got to a point where I’ve had 270GB worth of data taken out of material with samples. Then the Activity Monitor is still only at 40% with 700 or 800 tracks. It’s ridiculously powerful.

That’s amazing. Yeah, I don’t know what I would do without mine, to be honest with you. They’re just amazing machines. So tell us about some of your favorite libraries. Are you still using Bespoke strings?

Yeah. Spitfire Audio makes a particular set of libraries. And I was one of the original 25 people that we all sort of used to cost a lot of money. And we all put money in for these original strings. I own pretty well everything Spitfire’s ever made. That is because I have a remote studio in London. And that’s where Spitfire have recorded most of their libraries at AIR Studios. I know the sound of that room. It’s amazing. I worked in London with the London orchestra, and you have amazing engineers, like people like Jake Jackson and Simon Rhodes, who’ve recorded the stuff with amazing players in an amazing room. And you can hear it in the samples, and they have a humanity that a lot of the other sample libraries tend to be aesthetic in comparison.

You started out, if I remember correctly, in a studio using a Synclavier, right? And sampling off of that was in the early days, but you still have one, right?

Yes. I still have my Synclavier.

I love that. Are you so attached to it?

Actually, the original Les Paul. So if I want to save the 57th strap for me, it is my Synclavier. It sounds unique. I mean, in comparison, remember these things were insanely expensive whenever we compare what we’re doing now. When I first got into Synclavier, it was, I want to say, $5,000 a megabyte of RAM.

It’s amazing what has happened. So when you’re composing now, you’re composing using Pro Tools, you said, right?

Yeah, it’s a thing in film. The film world lives in Pro Tools. Everything after the composer is a Pro Tools world. So the engineers recording the orchestra record Pro Tools, the editors after it’s been mixed in Pro Tools, the sound goes onto the stage in Pro Tools. And I made a decision also, which was that when I was doing Avatar around 2009, we were looking, I had been using Logic earlier, Pro Tools started getting better MIDI, and Pro Tools just sounds great. I just think it’s significantly better than Cubase. And that’s a personal thing. I just noticed that when I put test sessions in Cubase and put them into Pro Tools and Logic, Pro Tools and Logic sounded much better than Cubase. And I know there’s a digital output and that everything is fine, but I just happened to hear something going on with the way that the sort of mix engine in Cubase. And other people may like it more. It’s undeniable that the MIDI control is better in things like Cubase and Logic. But Pro Tools has some advantages, especially with a film that I think to outweigh its disadvantages.

Do you want to talk a little bit more about that?

Linking machines is obviously one of the things that you can have multiple machines running. The other thing is that it means that when I go back and forth between pictures, changes are a big part of my life. And we then have to reconfirm our music to the picture. The great thing about staying in Pro Tools, it means that whatever conforming happens, I don’t have to convert across to Logic or to Cubase and reconform that then reconform everything back into Pro Tools. It’s effectively a unified standard for everything. And that’s really important to me because part of anything is that visceral feeling you get when you play. If I’m sitting at the Steinway and playing a Steinway, the Steinway system tells me whether I’m playing anything good or bad. And the same thing happens in terms of the way that you work in the studio. I play the studio, and the studio, If it sounds great, then if you know what you are doing, I find that it works better. It’s more creative for me than to have something that sounds great than the fact that I can tweak 11 parameters. Because I come from synthesizers, my day job was programming synthesizers for people when I was younger. So I understand that analogy very well. And therefore, a lot of the shortcuts that other people use, I don’t need to worry about them as much because I’ve lived that life for so many years.

How much of your work is analog?

None.

Interesting.

And that’s been true for a long time. I remember we were doing a film called The Amazing Spider-Man, where we did a test where we did everything, including mixing through a million-dollar console at Fox Studios. And then we did the same test, mixing everything digitally. And we decided we prefer the flexibility of running digitally, and that was in 2012. Basically, all of my rigs, apart from microphone preamps to record things into, everything else is digital. I was the guy that had tons and tons of analog equipment, I had all the vintage synthesizers, and everything, I still got some load in storage. But basically, all of that went away. Everything became computer-based. The only analogs I have are the converters to the loudspeakers and the converters from the microphones into my Pro Tools.

What are the most tracks you’ve worked with at any one point in time?

Probably 1100 tracks.

Oh my gosh.

Something like that. My starting template is around six or seven hundred tracks. Now it doesn’t mean I use six or seven hundred tracks, but I have them available. I know there are people who have many, many more than that but Pro Tools also has an advantage. It has a thing called Track Presets, which allows me to drag things in and out if I have exhausted everything, I only use it once in a while. I don’t have to keep them in my template. I can keep them separate and then just drag them in when I want them in very, very easily. But it’s probably six or seven hundred tracks, and there are all the major groups. So strings, brass, woodwinds, orchestral percussion, percussion, tuned percussion, synthesizers, keyboards, instruments, and vocals, and then there’s a whole thing for a choir. And then there’s all the other different bits and pieces that happened in film. So that’s normal for me anyway.

And you’re composing all of those tracks?

But I won’t use all of them. You won’t be using 600-700, but they are basically like your starting template, which means that I can choose to have every instrument that I want instantly. And I don’t have to sit there rummaging around trying to find things. And also, what happens is that when you’re working on a project, you’ll often create templates that you use because you have particular sounds that become key to that score.

Especially in film, too, because you’re varying the theme throughout the film sometimes, right? As well as creating music for the scenes.

Absolutely. Yeah.

So when you have musicians that come into your studio there, you’re recording them in Pro Tools. What codec are you working in? What are the files?

Well, everything we run is either 32 bits wavs, there’s really a 24 bit going in, obviously. And I’m using heavy matrix converters. Depending on what I’m doing, it’s either a 48K or a 96K.

Some of those old Martin sound converters don’t exist anymore. Do you have some old ones?

I’ve got two of those. I also use the Millennia Mic Preamps, which are wonderful. And then the Rupert Neve Designs have made some lovely, lovely stuff. So I have a couple of theirs as well, which are spectacular. But yeah, the great thing about a mic pre is it really never goes out of style. There are things that are 70 years

old, that still sounds amazing.

It’s funny. I’m not a musician, obviously, but I have a love for good headphones. And when Sony stopped making my favorite headphones, and a pair that I had were stolen, I was a little bit distraught, but they started making them again. I think it’s subjective; music is subjective. And that’s what makes it so wonderful because you are putting yourself out there every time you compose a new work, and some of your stuff comes from a very, very deep place. What did you like to do when you were five years old?

Five, I was probably playing with Action Man, but when I was 13, I pretty much went to the BBC saying how do I become a record producer, and how do I become a film composer? And so I’m unemployable in any other regard. So this has been the only thing I was capable of doing.

That’s amazing. But you’re doing what you love every day of your life. And I know you can’t talk about the new ones. But if we go on the internet, your bio is talking about a film called Brahmāstra. That’s coming out next year? Is that your music in the trailer?

No. Brahmāstra is very, very cool. So I have the curiosity gene; I like doing different things. And I’ve worked all over the world. I enjoy different cultures. And my agents said to me that there was this Bollywood series of films, a trilogy going to be made and they were really quite serious big budget. Not just by the budget, there had been in India, but even by Western standards, this is a pretty decent budget. And it is a spectacular movie. It’s obviously been delayed because of COVID–the first one. But young director, Ayan Mukerji, who is ridiculously talented, and it has without going into too much detail. I would say almost like The Lord of the Rings meets Marvel meets James Bond. I mean, it’s an action-adventure with mysticism. It is everything that you want from a Bollywood film. It also has some amazing songs. I’m doing the film score, but then every Bollywood film has to have songs; you are required to have the songs in them. And the songs have been written by this wonderful guy, Pritam Chakraborty, whose beautiful, beautiful songs. And there are the full-on dance numbers that you expect. And these incredible dancers as a part of a film. And coming from a Western perspective, this is unusual. You’re the middle of a chase, and then at the end of the chase, you go upstairs, and then a song breaks out. But it is done so beautifully, and I can understand, and they did their research so much. It really is fabulous. We were meant to finish this a long time ago. I’m hoping we’re going to finish it this year. And I’m hoping that it will come out next year. At least the first one, part one, will come out next year. Obviously, like every other film in the world, it has been delayed, because nobody wants to go to the cinema.

It’s always good to have the curiosity gene when in the music industry. You like to do different things and you want to keep exploring the world. Click To TweetThat looks like the kind of movie you have to watch on a big screen. You have to.

It really is. It’s got some fabulous action sequences, wonderful visual effects. It will look majestic. I hope they break out film for Indian cinema.

That sounds wonderful. I’m thinking here that in the theater, it’s going to be in beautiful Dolby Surround Sound, right? And it always bothers me when I see filmmakers, composers working so hard to make these beautiful works, literally works of music art, and then people are listening to them on their iPhones or watching them on it. It’s kind of in my mind, and it’s a bit tragic. But yeah, I think there were certain things that are meant to be seen in the theater. Now I’m curious about your live, The Birth of Skies and Earth, I wanted to try to find, so I could listen to it when I was thinking about interviewing you, and I wanted to listen to some of it. And I have not heard that it came out in 2019. And it was a huge undertaking. There were like what? Over 176 musicians on a stage and a 90-piece orchestra, choir, soloists?

Yeah, I work in China a lot. I enjoy Chinese culture, and the Chinese people are funny and creative. I have a number of projects there, and I’ve done several projects in Shanghai. And the city of Shanghai has a thing called the Shanghai Media Group, which is there to sponsor creative works. And they’ve worked with the Shanghai orchestra like they wanted to sponsor our commission who work based on China’s great myths and legends, of how China came to be. And it starts literally from the sort of the idea of there being chaos in the darkness, and nothing. And then you go from the nothingness of everything to the creation of the universe to the creation of the Earth to the heavens and the Earth, the sun and the skies. And then through to animals to phoenix’s and dragons and then the creation of music and art and writing and China itself. So they have all these different myths and legends that are things that the Chinese as people, generally everybody knows. And they wanted to make something that was a little less pure China because they could have just hired a Chinese composer. There are some amazing Chinese composers. But they said, “Well, we want something more international because the idea is that this may tour throughout the world at some point.” And so I was commissioned to write an oratorio. So it’s effectively like a mixture of an opera with a musical, but it’s on stage. And they gave me a libretto.

They gave me the lyrics which have been written beautifully by some of Shanghai’s finest poets who have written different lyrics in Mandarin. I then had to compose the score, and obviously, the choir and everything else, the parts for them to sing, everything had to be done in Chinese. So I don’t speak Mandarin, I can get around and pretty well, ask for a cup of tea and say thank you, and so on. But I couldn’t do better by the basis of it. So I then had to learn how to write music in Mandarin and not mangle it because you can have a situation where you have three characters, if you have one character, it might mean–now I’m making this up–might be a mountain you add a second character, might mean big mountain, you add a third character, it might mean cow. So one had to be careful that you connected the characters in a way that didn’t end up saying the great big cattle that is over the horizon. And that was the key, was learning how to write in Mandarin. Once I got that one nailed, then it was flashing a 96-minute piece of classical music.

It’s amazing that working in a foreign language that you don’t understand, and it would be very, very hard to get the emotional subtext and the rhythms, and also you’re dealing with the differences in the culture and how those people might react to things that perhaps as someone who was born and raised in England, might do it a little bit differently. I really admire what you did there. I can hardly wait to hear it.

It’s really good. Unfortunately, somebody may have recorded it, but it went on tour in China, but we never actually sat down and recorded it for an album, which I think is probably delayed; we may end up doing it one day,

Oh, that would be something that I really am going to hope that you can do. That’s amazing. So let’s go back to your room, and I’m soaring in the heavens with all of your work. I’m looking at all your credits while I’m talking to you. Back to your room, you’re composing on Pro Tools; you’ve got all your computers, you have your libraries, you have sort of your workflow that you’ve worked out for this current project. When you finish something, talk to us about the workflow from the composition side into your Pro Tools, and then how do you get it out, and where does it go from there?

So effectively, I’m creating, I have my keyboard. I create MIDI notes, or if I have musicians play, they create audio files, and then I convert those. So I’ve made a demo, so I’ve got something that now has a fake orchestra on it, and it sounds very good because the samples are very good. And I’ve mocked it up against the picture or whatever I’m working on so that I have something decent. At this point, I hand it over to the grown-ups. I know people who are significantly better orchestrators than I am. Although I can get away with certain things, I think that having somebody who makes sure that they actually survive somehow generated between the chosen and it doesn’t work there are better than they should be. Although I mapped out a lot of the paths, the orchestrators will then spread things out, so things are better. And also, it allows me to get on to do what I’m paid to do, which is to write music, and orchestration actually getting along with this. The next thing we have to do is we prep the files so that I can record it with a live orchestra, for instance, if I’m using an orchestra. The orchestrators, we’re all linked to using all of the normal media transfer systems that everybody uses and where we have been used to working this way for probably seven, eight years, maybe longer. This is not anything new.

So I have a team of people who quite often don’t see each other for months, partly because I did so much traveling last year, but also because we found that working at home was perfectly good. I have people who work with me, in terms of everybody else, we have worked out how to do this sort of remote working environment has been part of our normal work for a long time. So everything gets handed over to orchestrators; they then prep files in a thing called Sibelius, which allows us to create the sheet music. And we provide the Pro Tools sessions, so they can be recorded at a big studio, if it was in Los Angeles, it would be Sony or Fox, if it was in London, it would be Abbey Road or AIR studios or if it was in Vienna, or Bratislava, it could be a number of different places around the world. But it doesn’t matter where you are around the world; the orchestra still has to play black dots on a piece of white paper. And so we have to have the old ways of creating those, then that’s printed out for the orchestra to play. And I hope that I’m there when the orchestra is recording, but it is often the case where I will need to remote in, and I’m using software like Source-Connect, for instance, or so on to remote in to listen to the orchestral recording, and also it will be good to talk to a local conductor because I can’t be there. And the local conductor literally has me in his or her headphones, and I can tell them what they need to do, and I can make changes on the fly. And it works seamlessly, and we’ve been working on that way for many years. I can’t actually say that, in terms of my workflow, the COVID has really made any difference at all.

Well, that’s good to hear.

It’s made a difference to the recording process, but in the composition, not much. But the recording process has been terribly affected, and the lives of musicians have been decimated. Because if you can imagine where the film’s go, you might have up to 100 musicians in a room. Now, if you’re lucky, you can get 40 players into a live studio. And there are whole extra things about breaks about making sure that you cannot record, wind players and brass players have to play isolated separately from any other musicians. Choirs, likewise, everybody has to have a three-meter gap between them. So there are huge restrictions out, and that’s notwithstanding the fact that all the major orchestras may go bust.

Music comes really from the heart, from the soul, from the mind, and doing it in isolation. I know when you’re composing, it’s different, but like you’re saying, when you’re recording musicians, there’s something about the energy in the room with a 400 voice choir all in the same room with one conductor. And then those notes are resonating, and the overtones are resonating. It’s just an amazing feeling for the performers as well as I’m sure for you. Larry O’Connor, who owns OWC, says you’re just amazing to work with. And I imagine that that is another reason why you’ve worked on over 400 projects because you have to be able to play with others well in order to make all of this work in the current settings. How does OWC and the equipment other than you have some memory, right? And you have the SSDs to beef up the storage capability within your machines. Do you have other OWC equipment for external storage or any servers? What are you using?

I’ve got generations and generations of OWC stuff. So I have ThunderBays that go back to neanderthal times were spinning hard drives and stacks of big ones and little ones. When SSDs came out in the two and a half-inch format, then I was using box; they’re taking the little mini ones. And that was transformative because it meant I could carry libraries with. Previously we were running external RAIDS, and they became bigger and heavier and noisier, and everything else, and suddenly these little boxes could outperform them. And why for instance, the Accelsior cards are working so well for me in terms in my new Mac Pro, is that it allows me to have a system now where I don’t have all these boxes hanging off the outside of my Mac Pro as much as I love the trash cans because they were very compact and transportable. The problem was you ended up with this spaghetti of stuff that was running off them. The 4M2s were great because they were the first time I could get the NVMe up to size to like, actually get some NVMe RAIDs that were big enough for me to use them properly. And then, of course, I’ve got all the sort of hubs. The different Thunderbolt 3 and Thunderbolt 2 hubs that I’ve had for years. I mean, I’ve been buying stuff from OWC for 15 years. I’m going to guess since it first appeared, it was the place where I would buy all the bits and pieces. And Larry’s wonderful. But I also know that when we were having some issues, there was a bug in the 10.15.4 Apple release of Catalina that was affecting large data transfers. And the guys at SoftRAID and the guys at OWC worked tirelessly with me to try and solve. We nailed it down with a fix, and the guys could not have been better. I think that’s the thing that I would say about OWC, and the reason I agree to talk to you about it is that they’ve gone the extra mile. And I think that for someone like me, that’s worth in gold.

It bothers me when I see filmmakers and composers working so hard to make literal works of music and art, then see people watching or listening to them on their iPhones. Click To TweetYeah, they’re amazing. I think I have some OWC equipment that looks like it was developed in the time of the Flintstones, and it still works. It’s amazing. And hard drives are susceptible to well, they just sometimes have problems, or sometimes they die. I’ve been on location, and OWC got on the phone, and immediately, when SoftRAID said I might be losing a drive, they immediately shipped me another one. And I could continue working without missing a beat and felt confident that I wasn’t going to lose anything. The SSDs are wonderful, but you do have to back them up. Because if for some reason you lose one, it’s gone. They’re very hard to recover, right?

Yes. I look at SSDs as something that needs to be backed up every day, just in case. Because the thing with spinning drives, I could use our studio; even with braids, there is some software that we could dig into it and get stuff out. But you just can’t do that with SSDs. If it doesn’t exist twice, it doesn’t exist.

Well, the good news about using SoftRAID is you can verify every drive before you start using it. And that’s a leg up for all of us. It’s amazing. And the SSDs are just screaming fast compared to the spinners, right?

Yeah. I had two 8TB of Accelsiors, and then Larry told me that they were making 16. So I bought two of the 16. So I have 32 terabytes of those inside the Mac Pro. And they’re both running at six gigs a second. And I don’t read them together. I’ve got them running as two separate 16s. And the best thing I can say about them is they’re anonymous. The moment I have to think about it and then there’s a problem. And the other thing I could say is that I had a tech support call with a company yesterday, where there was a problem with their software. And we were loading up probably four or five gigs worth of samples into this piece of software. And I was screen sharing with the tech guy. And the tech guy literally was saying, and I just can’t believe how fast this is. I cannot believe how fast this is loading. And he said that we may actually have a problem, which is I may be loading my samples faster than they’re catching up with it. And he was wondering whether that might have been a problem. He said, “We will load this, and then we’ll wait a couple of minutes.” and five seconds later, he was watching this thing blister through. And for me, the reason I bought these RAIDS is that it’s seamless, it allows me to work faster. That’s obvious. When you multiply the amount of time you say, by loading, because a load takes say 10 seconds instead of two minutes. When you add that across a day, in a week, and a month in a year, that’s a huge amount of time that I don’t have to think of watching a progress bar. And that, for me, means these things are hugely worthwhile. I’m not dealing with 8K video files. I’m dealing with millions and millions of samples. And it’s a different sort of thing, but it is the load times become a real issue.

When you're creating and your mind is moving really fast, you need equipment that's going to keep up with you. Click To TweetAnd also, when you’re creating your mind is moving really fast, you need equipment that’s going to keep up with you, right?

Yeah, I don’t want to have to think about those.

I just want to thank OWC for sponsoring OWC Radio and allowing me to meet wonderful artists like Simon. And Simon, have a good trip back to London when you go, and when you can talk about your new project, please promise me I’ll be able to speak with you again. We just love your work and are so pleased that you’re there. And there’s so much for us to talk about. So we’ll table the rest of it another time. And everyone listening like I always tell you, you get up off your chair and you go do something wonderful today. This is Cirina Catania, and I’m signing off.

Bye bye.

Important Links

- Simon Franglen

- Simon Franglen – IMDb

- Simon Franglen – Facebook

- Simon Franglen – Twitter

- The Birth of Skies and Earth

- Ayan Mukerji

- Jake Jackson

- Larry O’Connor

- Pritam Chakraborty

- Simon Rhodes

- Avid Pro Tools

- Cubase

- Dolby Surround Sound

- Logic Pro

- macOS Catalina

- SoftRAID

- Source-Connect

- Spitfire Audio

- Track Presets

- Vienna Ensemble Pro

- Avatar (2009 film)

- Brahmāstra

- James Bond

- Marvel

- The Amazing Spider-Man

- (2012)

- The Lord of the Rings

- Abbey Road

- AIR Studios

- Fox 20th Century Studios

- LG

- Mac Pro 2019

- Millennia Mic Preamps

- OWC Accelsior 4M2

- OWC Envoy Pro EX

- OWC Express 4M2

- OWC ThunderBay 4

- OWC Thunderbolt 2 Dock

- OWC Thunderbolt 3 Dock

- Rupert Neve Designs

- Sony

- Synclavier

- Yamaha 88-Note Keyboard

- The Flintstones

Checklist

- Just get started. Don’t wait for inspiration to hit you when creating music. Sometimes it doesn’t come and all you have to do is keep creating until you land on something good.

- Be flexible and prepare yourself to make music anytime. Again, we don’t know when inspiration will hit us. But when it does, it’s better to be prepared. Carry around a notebook and pen or a recorder wherever you go.

- Be familiar with other classifications of music. Develop an eclectic taste so you can depict which types of music best suit your style and can play around with other genres.

- Change things up a bit once in a while. It’s good to keep exploring different tempos and styles but make sure to keep adding my signature flair. This will keep my audience curious and entertained.

- Don’t be afraid of getting outside your comfort zone. Aim to reach new heights and never settle.

- Invest in high-quality audio composition and editing equipment. Musical instruments, computers, and heavy-duty SSDs are just a few of the things a composer needs to keep an archive of his creations.

- Build or work in a studio that has eliminated distractions. Make sure that it’s soundproof so you can produce good quality music.

- Invest in audio libraries. This will make your scoring and audio mixing tasks a lot more efficient.

- Remain authentic and keep true to who you are and what your signature style is. The goal is that whenever people hear your music, they immediately know that it’s you.

- Check out Simon Franglen’s website to learn more about his works of art.